The Victorian age was a heroic one, so much so that it produced an oversupply of heroes. Countless intrepid individuals roamed the Earth, scouring every nook and cranny for an opportunity to become the next grand conqueror, inventor, or explorer. And while some discoveries pushed humanity higher and further, others faded from the pages of history before the ink could even dry. Our protagonist was the latter type, having masterminded the world’s most creative technology for transporting Egyptian obelisks. Here is how to do it.

Step One: Find an Obelisk

This was perhaps the easiest step in 1875, considering that everyone and their brother flocked to Egypt, the homeland of obelisks. This certainly was the case of British engineer John Dixon, who dropped by on a visit to his brother, only to stumble (quite literally) upon an obelisk that lay prostrate in the sand, a nuisance rather than an attraction. Once gifted to King George III by Egyptian viceroy Muhammad Ali, the oversized relic’s mass and shape had deemed it impractical and expensive for transportation.

Anyone with a large family knows how to handle an awkward gift – smile and say “thank you”, then pretend you forgot about it. Courteous as ever, the British did the same, and the marvelous artefact obstructed Alexandria’s picturesque traffic for a few decades longer.

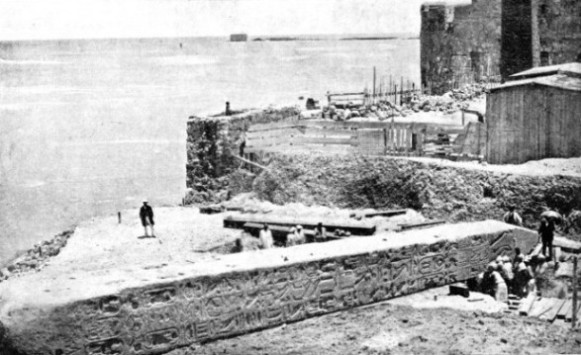

Step Two: Dig

Having spent the better part of two millennia toppled in the sand, the obelisk was half-buried in that tricky material, close enough to the beach but almost impossible to move in one piece. Previous attempts had only confirmed that angular objects rolled with difficulty, and while digging ancient stuff out of the sand was already a mundane activity in Egypt, the art of overcoming the laws of physics had somewhat rusted since the pyramids. In 1877, John Dixon returned to Alexandria with a firm intention to change this, bringing some rather unorthodox equipment for the purpose.

Step Three: Roll

The Thames Ironworks in Blackwall advertised themselves as experts in unconventional constructions. Still, John Dixon must have been quite entertained by the expressions on the principals’ faces, when he first walked in and pitched his project. He must have done a good job, though, for on his second trip to Egypt, his colossal luggage included one of the most bizarre and innovative floating structures ever seen.

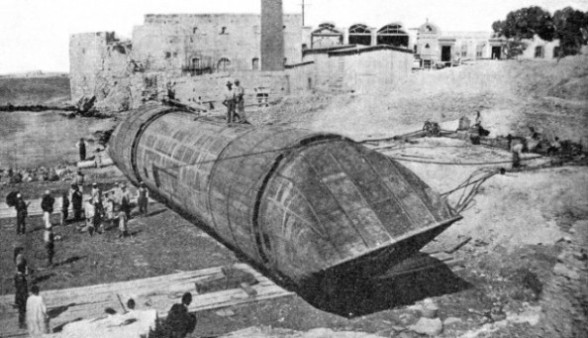

After having the obelisk dug out of the sand, the Dixon brothers clad the entire behemoth in an iron cylinder, until it became just the right shape to roll down a gentle slope to the waters of the ancient harbor. In front of an audience of curious expats, awed children, and sun-dazed loafers, they completed the iron cylinder to its final form of a seagoing vessel – the Cleopatra.

Step Four: Transform

When she slipped out of the Egyptian Admiralty’s dry dock, the cigar-shaped wonder was 92 feet long, 16 feet wide, and offered enough cabin space for a captain and three crewmen. The cargo was well provided for, too, with several round bulkheads supporting the metal structure and stabilizing the obelisk. And while the Cleopatra (disappointingly) had no propulsion of her own, she still boasted her own rigging and steering to help her keep steady on the waves. A cylindrical cutwater fore and a tiny hurricane deck aft completed the superstructure of that noblest of all pontoons.

All in all, the Cleopatra was not a mere oddity – from an engineering viewpoint, she was a respectable seagoing structure. The list of her shortcomings, though, was topped by a clumsy steering, making the vessel unwieldy and putting the steel towline under extraordinary strain. Such factors were only expected to cause a problem in rough waters, and no swell was big enough to intimidate a Victorian hero. But the sea, as always, had a cruel sense of humor.

Step Five: Mess Up

As history had so often shown, self-sabotage was the most effective variety. After centuries of advanced navigation, every old salt knew that autumn crossings in the Bay of Biscay were a gamble, not to mention for a novel and untested craft like Dixon’s. And while the Cleopatra only wobbled a bit as the steamer Olga tugged her out of Alexandria on a clear September day, the Atlantic was a whole different kettle of fish. As soon as the bizarre couple sailed past Gibraltar, the ocean clutched them in a violent grip, and the vessel’s shortcomings remained hidden no more. The bow’s design proved effective at the beginning, the cutwater keeping the deckhouse dry enough, but as the storm grew to frightful proportions, Cleopatra’s limited maneuverability left her helpless amidst the monstrous waves.

To the horror of the crew, a violent surge to the side shifted the ballast and tipped her over. Fast and decisive, Captain Carter ordered the men to cut down the mast, but that failed to stabilize the jolting vessel. In a desperate attempt, Captain Booth of the Olga sent out a rescue boat to Cleopatra, but another wave smashed into it, sending the boat and her six men to the bottom. With no other way out of the nightmare, Booth made a decision no master ever wants to face, cutting the towline and setting Cleopatra adrift.

Step Six: Hope

One can only imagine the horror and despair of Captain Henry Carter and his crew, as the lifeless Cleopatra drifted through the gale. After watching the six men from the Olga vanish in the raging ocean, they must have expected a similar demise. But as the waves calmed down and the wrathful sky began to clear, a dark spot emerged on the horizon. As the spot approached, it took the shape of a steamer, and when she got close enough for the worn-out survivors to read the name Fitzmaurice on the bow, a towing rope splashed in the water near them. A couple of days later, the Galician port of Ferrol welcomed a battered iron cylinder with a massive obelisk hiding in the holds.

Step Seven: Reset

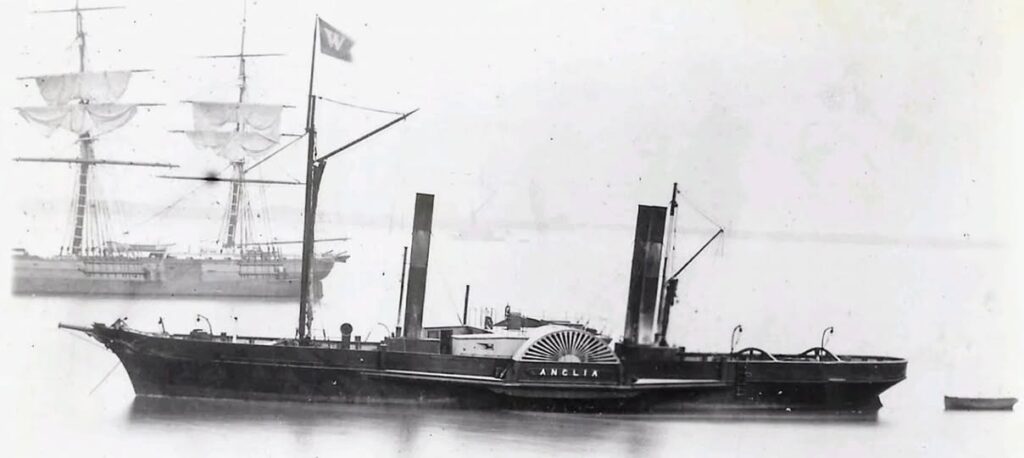

While Dixon and his investors were dealing with the consequences of the disaster, including an astronomical salvage claim from the Fitzmaurice, the Cleopatra was undergoing extensive and costly repairs at a Spanish dry dock. When she finally tasted saltwater again, the project had enough financial support to reach completion. Pulled along by Anglia, London’s largest towboat, the obelisk made its slow and clumsy way toward Britannia’s beating heart.

Step Eight: Admire

On 12 September 1878 in London, Cleopatra’s Needle finally took its intended vertical position and assumed its intended function – to attract the admiration of generations to come. Shortly after, the extravagant vessel that brought it all the way from Egypt was broken down at the scrapyard.

Was that perilous exercise worth the money? In the context of the insatiable Victorian appetite for glory, probably yes.

Was it worth the six lives lost at sea? Not in a million years.

Want to read about more strange vessels? Click here!

The Shipyard