We were taught to imagine Columbus’s arrival in America as a glorious moment in human history, a cornerstone of modern civilization. After all, isn’t the discovery of a new continent every explorer’s dream? For many Europeans at the time, however, the Americas were a great nuisance – a colossal landmass standing in the way of global trade, halfway between Europe and Asia. In fact, many saw the accidental discovery as such a grandiose blunder that the Italian explorer kept insisting the Caribbean shores were the west coast of India.

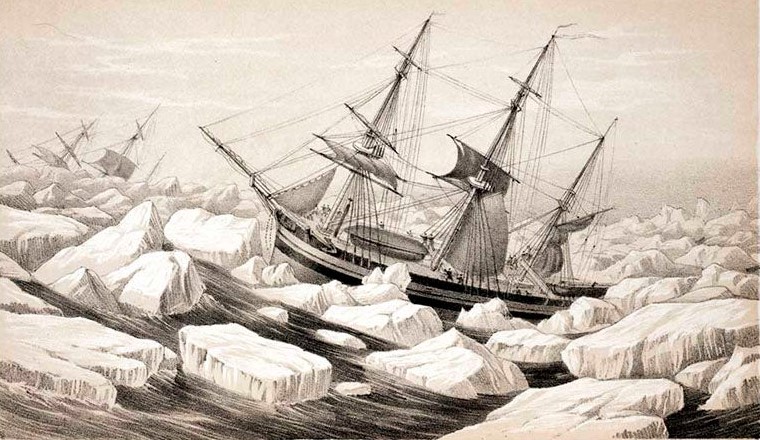

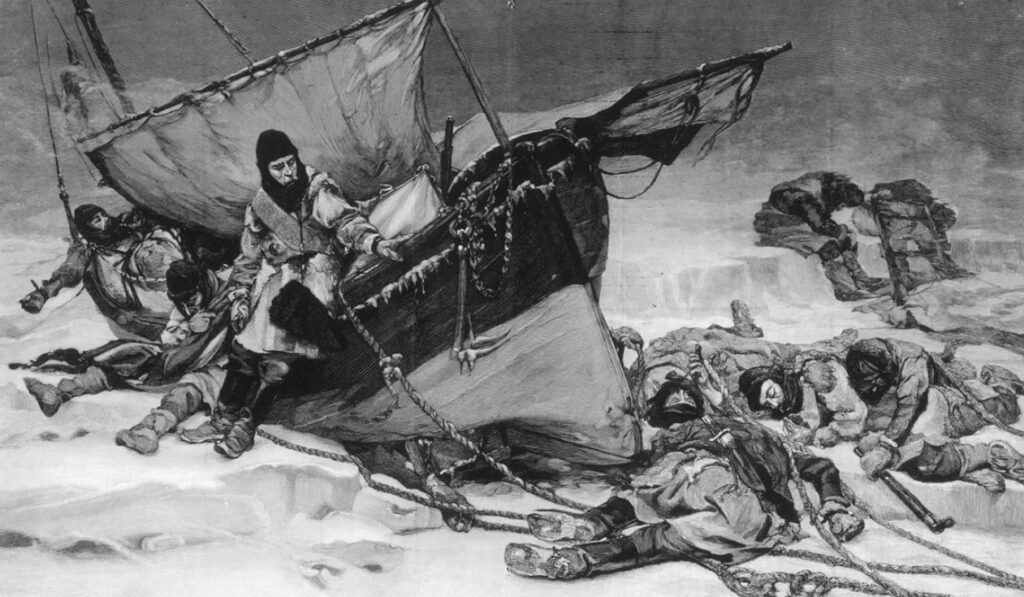

A few decades later, seafarers were resigned to the existence of that unexpected continent and rolled up their sleeves to find a passage through it. And by “rolled up their sleeves” I mean they blindly sailed into the Arctic, where Nature in her most savage incarnation awaited them with claws of ice and a vicious temper. This is the story of one of the most thrilling, gruesome, and unforgiving quests in maritime history.

Trade War (Neither the First, nor the Last)

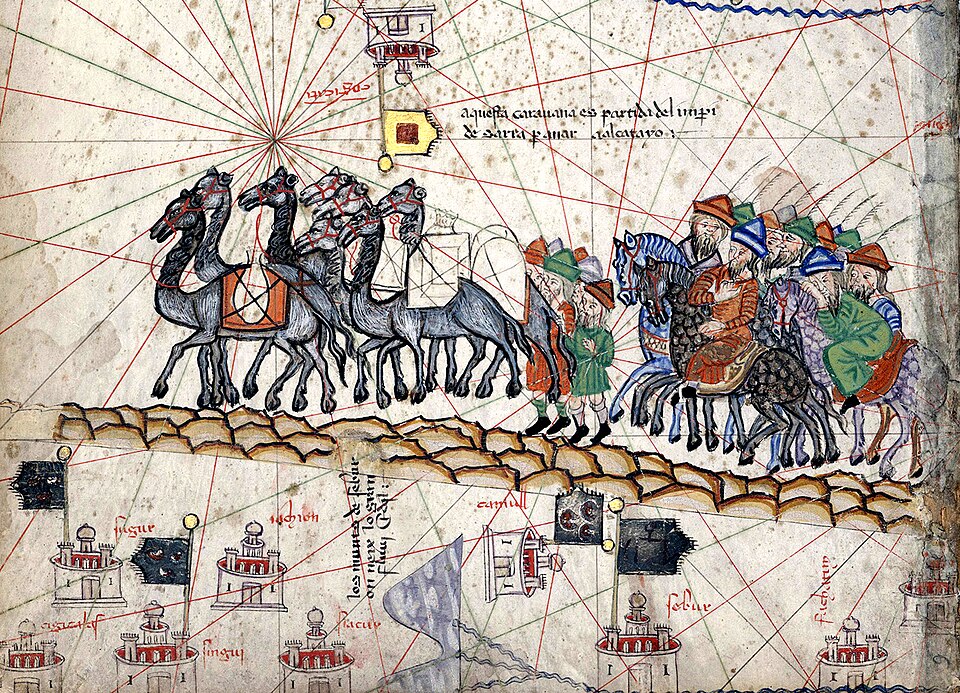

Medieval European geographers believed there was a direct westward route to India and China, a convenient circumvention of the Silk Road, but the stability of Pax Mongolica in the 13th and 14th century discouraged people from taking to the sea. True, the Silk Road was slow and expensive but why fix something that had worked for so many centuries? The situation took a dramatic turn in 1368, however, when Ming forces expelled the Mongols from China, allowing overland trade routes to descend into chaos and disrupting supplies to the European market. Then in 1453, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II sat on the Byzantine throne in Constantinople, monopolizing the Western section of the route and further isolating Europe from China.

The Age of (Accidental) Discovery

The triumphal mood of Columbus’s arrival to the Caribbean in 1492 lasted only while he and the Crown of Castille believed the newfound tropical paradise was the coveted India. The awkward but inevitable realization blossomed into a full-blown crisis six years later, when the Portuguese arrived in what was truly India, making the Spanish look like the joke of the century. And as said century drew to a close, locating a passage through America became a matter of survival.

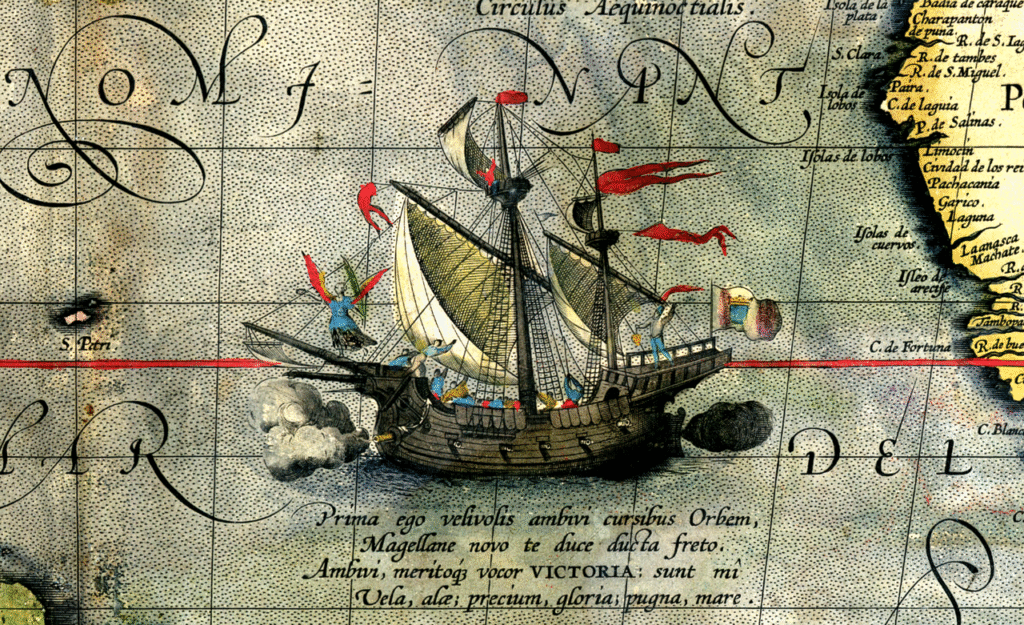

The journeys of Venetian explorer Giovanni Caboto (or John Cabot) left precious few records, with historians now scratching their heads whether the great man died near Newfoundland in 1499 or returned to his adoptive homeland of England. Two decades later, Magellan’s voyage provided a general outline of the coast, proving that the new discovery was one giant obstacle. Somewhat wasp-shaped, the contiguous land mass of the new continent thinned around the middle, but the narrow isthmus there was covered by a jungle so impenetrable that most explorers preferred the peril of the open seas. The route further south was no better – despite Magellan’s discovery of the straits at Tierra del Fuego, the rough seas bashed all hopes for regular merchant crossings. The only option left was north.

Armed with this shaky knowledge, Jacques Cartier took the French king’s commission to sail to North America and locate that passage to India everyone was talking about. With the notable exception of founding Quebec and bringing s few native chiefs to France to meet the king, however, Cartier’s voyages were also inconclusive. At about the same time, Spain was trying from the other end, with the formidable conquistador Hernan Cortez dispatching Captain Francisco de Ulloa on a mission north from Acapulco and around the island of California, in search of the mythical strait to the Atlantic. Ulloa never found the strait but made an essential contribution to the map of America by pointing out that California was, in fact, not an island.

Into the Ice

Led by the speculation that the continuous sunshine of the Arctic summer would melt the ice cap and allow unobstructed passage, Henry Hudson departed England in 1607 to lead a small expedition on behalf of the English Muscovy Company. The world’s first joint-stock corporation was determined to locate an alternative route to Russia and the Far East, one that was not brimming with Dutch, Spanish, or Portuguese competitors. Navigation was a bit troublesome in those days, though, and Hudson first sailed to Greenland, only to turn east later on, reaching Spitsbergen, then inched north until the ice prevented further progress.

Hudson made another attempt two years later, this time employed by the Dutch East India Company, and with clear instructions to cross the Russian Arctic into the Pacific. Predictably to Hudson, who already knew how the Arctic worked, the polar ice had a mind of its own and blocked the way. The Englishman, however, made a bold decision to disobey orders and took a westward course toward America, reaching Nova Scotia in midsummer. After a skirmish with the locals, Hudson made his way into Chesapeake Bay, locating the river that later on took his name. For reasons only obvious in hindsight, the river failed to reach Asia, but the Englishman blazed a trail for the Dutch colonists that settled the area and founded the city of New Amsterdam (present-day New York).

Time For Tragedy

It took Europeans some time to realize that this dreadful landmass was more than an obstacle on the way to China – it was rather a treasure trove on its own. By the end of the 17th century, with the help of firearms and certain germs, the Americas underwent extensive colonization, putting the search for the elusive passage on hold. But when the American War of Independence deprived Britain of its most prized colony, the Asian trade regained its vital importance, prompting the Royal Navy to resume the efforts to locate it.

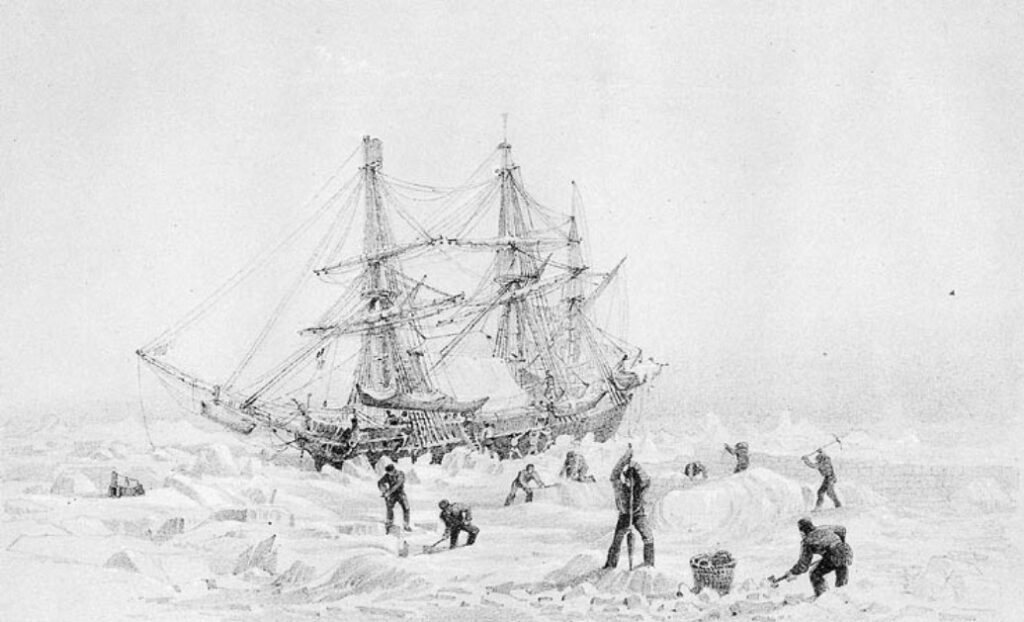

With the Industrial Revolution now under way, the 1845 expedition was a case study of modern technology, deploying two steam-powered ships, Erebus and Terror, both with reinforced hulls for polar service and internal heating for the inevitable wintering amidst the ice. And speaking of winter, the holds of the two vessels carried tons of canned food, a revolutionary technology at the time.

The man who led the expedition had the credentials to match the scale. The 19th century abounded in major wars, and John Franklin had been in most of them. Out at sea since the age of twelve, he had seen action at Copenhagen, China, America, and Trafalgar. That being only the start of an illustrious career, Franklin later became a seasoned Arctic explorer, with several successful expeditions to Spitzbergen and Canada. Such careers, however, often turn from glorious to gruesome, and Franklin’s was one such case.

The expedition departed the English shore in late spring, and their quick stopover in Greenland was the last time they were seen by European eyes. For the next three years, no news from the expedition reached Britain. By 1848, even the most optimistic members of the Admiralty were getting a bit antsy, especially as Franklin’s wife took the initiative and urged the leadership in London to pluck their heads out of the sand and do something. It worked, eventually, and three expeditions set off in search of Erebus and Terror, one overland, one sailing into Canada’s Arctic Parry Channel, and the third one approaching from the Pacific.

After four years of painful progress through ice-clad wastelands, overland leader John Rae met a group of Innuits, who told the unsettling story of Franklin’s expedition. Four years prior, the native tribe had spotted a group of white men hunting deer not far from two ships vised in the ice. The following spring, the only remains of the foreign intruders had been their half-frozen and cannibalized corpses. The news caused an outcry in Victorian Britain, with public opinion so outraged that Franklin’s widow had to commission Charles Dickens to write an open letter, denouncing Rae as a fraud. Refusing to believe Rae’s findings, Lady Franklin devoted the rest of her life to her own expeditions, which, if anything, only confirmed the frightful story. In 1859, one of those expeditions discovered a cairn with a note hidden inside, reporting of Sir Franklin’s demise and the disbanding of the group.

It was not until the 21st century that the mystery was finally pieced together by modern science. In the 1980s, explorers discovered lead-poisoned human remains from the expedition and sloppy lead welding seams on the cans left behind by the expedition, hinting that at least some men died of toxicity, while others starved to death due to mass spoilage of the food supplies. The ships were only discovered a few years ago, Erebus in 2014 and Terror in 2016, corroborating the statements of local Innuits and Rae’s reports to the Admiralty.

Ski Season

If there ever was a person north of the Arctic Circle to deserve the title of b@d@$$, that surely must have been Roald Amundsen. One of many “firsts” in the career of the single-minded Norwegian was navigating through the entire Northwest Passage in 1903. Perhaps appalled and cautioned by Franklin’s catastrophic demise, he decided to do exactly the opposite: no scale, no cutting-edge technology, no years’ worth of provisions. Amundsen’s expedition of six rugged men fitted neatly on a 21-meter fishing boat, propelled by a tiny 13hp diesel engine. Instead of fretting over dwindling rations, the explorers learned from the Innuits all there was to know about survival in the local ecosystem. And while this approach meant giving up canned Norwegian delicacies, it allowed the crew to manage two robust winters on King William Island.

Amundsen followed Franklin and Rae’s route through Baffin Bay, Parry Channel, Peel Sound, James Ross Strait, and Rae Strait. After two years of bitterness, the crew completed the passage and dropped anchor near Hershel Island. In true Nordic fashion, Amundsen pulled out a pair of skis from his luggage and skied to the nearest settlement. That just happened to be the town of Eagle in Alaska, some 800 km away! Not only did Amundsen get there alive and sent a telegram back home, he also skied back to his ship, proving that a) a Northwest passage existed, b) the passage was, as suspected, not a realistic trade route, and c) some people were simply built different.

Here Comes the Sun

As with the Northeast Passage through the Russian Arctic, what opened up the Canadian route was not an intrepid adventurer but global climate change. As the polar caps continue to melt at alarming rates, the warmer Arctic summers are finally opening up a seasonal pathway through the deadly straits. 2007 saw the first passage of a merchant vessel without an accompanying icebreaker, while in 2016, the Hong Kong Genting Line sent their cruise ship Crystal Serenity on a 28-day pleasure voyage from Vancouver to New York. But despite the curiosity factor in such initiatives, the ice is likely to stay for a while, making commercial navigation too unreliable for the time-sensitive schedules of modern trade.

Enjoyed this post? Click here to read about the Northeast Passage!

The Shipyard