Concrete ships, concrete ships, concrete… I repeated the phrase a few times in my mind, each time sounding more and more improbable. After all, isn’t the excellent sinkability one of the most notable characteristics of this material? But believe it or not, ships made of reinforced concrete existed for several decades, crossing both the Atlantic and the Pacific and even playing a crucial role in the D-Day landings. In fact, concrete hulls proved so durable they became some of the most iconic shipwrecks around the world.

The Idea

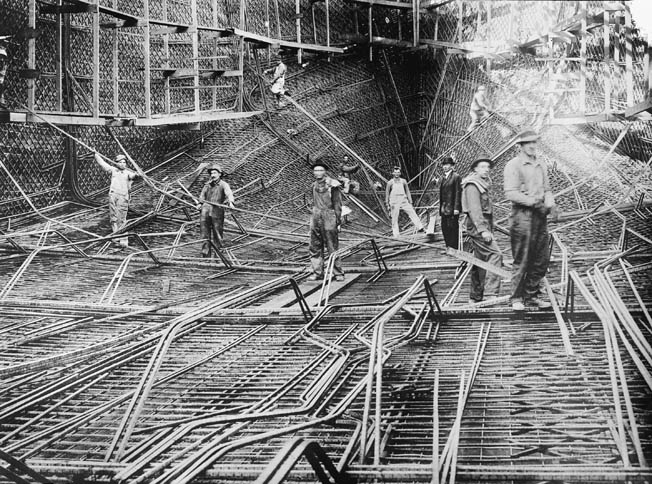

Why not? This question has always ignited the enthusiasm of inventors, and Joseph-Louis Lambot was no exception. His logic was that any material should be able to float, as long as it was shaped like a hollow body and displaced enough water. Not only this, but ferroconcrete was also three times less dense than steel and infinitely more resistant to saltwater corrosion. Finding no theoretical objections to his idea, the Frenchman rolled up his sleeves and produced a small prototype for the 1855 World’s Fair in Paris, where it managed to raise more than a few eyebrows.

The Stillborn Fleet

Although Lambot scrapped the project soon after, others took the baton and produced a number of experimental designs in the following decades – river barges in Germany, self-propelled boats in Italy, as well as the Norwegian seagoing steamer Namsenfjord. The latter hit the waves in 1917, just as the United States hit the war, and with so much of the Entente’s tonnage headed for the bottom of the ocean, steel supply got a little tight. No measure was desperate enough, and the US Navy hired Nicolay Fougner, father of the Namsenfjord, to design the world’s first fleet of ferrocement emergency vessels.

Fortunately for the world and somewhat disappointingly to Fougner, the Great War ended before his grand vision could be fulfilled, with only half of the 24 planned ships completed and not a single one seeing combat. No ship is ever useless, though, and the orphaned vessels had careers more original than getting sunk in a world war.

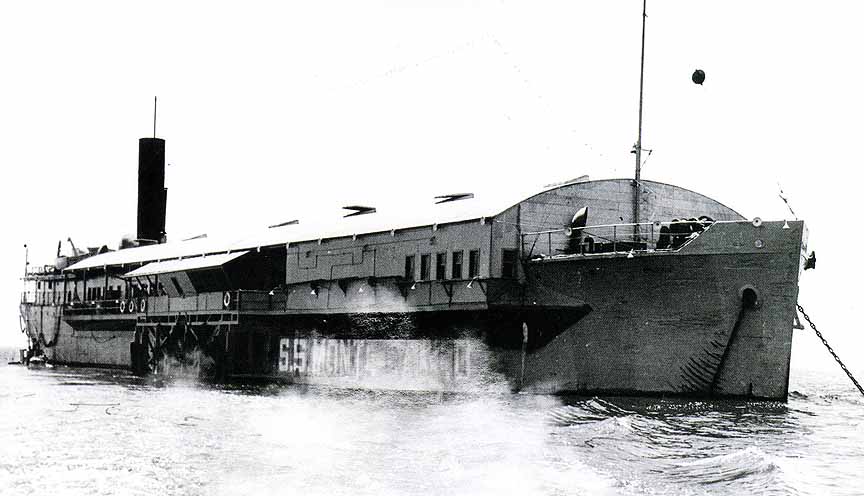

The SS Monte Carlo, for example, served as a floating sin city during Prohibition – a haven of gambling, prostitution, and drunkenness. She had always been a pesky one, having broken loose from the slipways of the Newport Shipbuilding Company before the workers could clear the area, injuring twelve in the accident.

The new job off the balmy coast of California seemed to fit her well, with music blasting in her spacious dancing hall and booze-drenched couples wandering like shadows through the smoke-filled lounges. On a quiet off-season night, however, a storm broke her moorings, and she drifted toward Coronado beach, where she remains until present day, battered by the elements but still holding on.

A similar life awaited the SS Sapona, built by the Liberty Ship Building Company and retired before she could sail to battle. When Prohibition boosted demand for bootlegging facilities, the Sapona discovered her vocation as an offshore liquor warehouse. Her owner, one-armed British war veteran Captain Bruce Bethell, ran a lively rum hustle out of the Bahamas, so he scuttled his new toy a convenient distance from Miami, filling her every nook and cranny with rum barrels. The arrangement did not last long – a vicious storm in 1926 battered the hull hard enough to break off the stern, making Sapona so hazardous that Bethell’s partner drowned during a visit, while the Captain himself barely made it out alive. The rest of her proved sturdy, though, and the old wreck is still a popular diving site.

After a troubled start as a tanker and bulk carrier in the 1920s, the SS San Pasqual was sold to a sugar manufacturer in Cuba, where she was run aground and also used as a warehouse. She was already settled into this humdrum occupation, when the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and America was at war again. Cuba then joined the Allied camp and lent the sturdy San Pasqual to the US Coast Guard to use as a logistical base. Transformed from ruin to citadel, she bristled with two cannons and six anti-aircraft machine guns. Built for a Great War she never saw, only to have her corpse revived for the second round – many at the time must have smiled at life’s exquisite sense of humor. But those wars are now both in the distant past, while the San Pasqual still stands proud at the same spot.

The Big Crossing

The most distinguished ferrocement ship of the WWI vintage was SS Faith, built in 1918 by the San Francisco Shipbuilding Company for a private owner. Unburdened by heavy government procedures, Faith was the first US concrete vessel to be completed, well ahead of the Emergency Fleet. With a length of 336 ft and nearing 3,500 tons, she was a proper ocean-going steamer, albeit a bit on the hefty side. To offset this shortcoming and make her less top-heavy, much of the superstructure was wooden, including the bridge, main deck, and forecastle.

Hers was a classical silhouette with an imposing stern, pining to cut through ocean waves, and boy did she! An eighty-mile gale greeted her on her maiden journey, but while other ships dashed for the nearest shelter, Faith completed the voyage with her signature slow and steady pace. After plying the Pacific coast of the Americas for a few months, she changed owners and was dispatched on a historic journey. In August that year, sailors and workers at the Surrey Commercial Dock in London paused for a minute to watch an unusual vessel enter the harbor – SS Faith had just become the first concrete ship to cross the Atlantic. Another change of ownership followed, and soon she was back in the States, the only one of her kind to make the round trip.

Although lauded for low vibrations and tame behavior in heavy seas, Faith did not survive the post-war economic turbulence of the 1920s. An unstable economy is a ship’s worst enemy, and the experimental fleet was even more vulnerable than the rest. Without government aid to bridge efficiency gaps, the novel vessels were too expensive to run, many of them ending up as extravagant breakwaters and embankments. SS Faith was no exception, finding a final resting place in the Mexican Grijalva River.

Sunk to Live Forever

After their devastating track record in the Great War, German U-boats returned with a vengeance in 1939, sending 3,000 Allied vessels to the bottom of the sea over the course of WWII. Despite the awkward memory of the Emergency Fleet, the USA and Britain were forced by steel shortages to give reinforced concrete another chance. The US government commissioned 24 seagoing merchant vessels, while the British completed 12 tugs and 495 barges. And while a few of these can still be found here and there, the ones that made history were the SS Vitruvius and SS David O. Saylor.

No one at their launching in Florida thought that either vessel would ever see any action, after a serious miscalculation of the ballast caused cracks in the hulls, deeming both vessels damaged and hazardous. In April 1944, however, the two sisters joined a mysterious convoy of damaged freighters and steamed across the Atlantic to the European front. Once in Britain, the mystery continued, as they all shed their equipment and furnishings but gained enough explosives in the holds to sink them when the time came.

On June 8, two days after D-Day, two portable harbors began taking shape near Omaha Beach and Arromanches. The inner sections of these so-called Mulberries included a number of scuttled ships, two of which were the Vitruvius and David O. Saylor. In the course of the invasion, the ingenious structures allowed massive Allied vessels to unload two million men, four million tons of materiel, and half a million vehicles.

But as wars are often governed by Murphy’s Law, 19 June 1944 saw the worst summer gale in 40 years, decimating the Mulberry at Omaha Beach and leaving Allied armies with just the one at Arromanches, where the two concrete sisters held the fort until the end. And just like many of their underappreciated brethren, both Vitruvius and David O. Saylor can still be seen, half-submerged near the shore, all but forgotten.

The Shipyard