Raging for ten gruesome years combined, the two world wars caused unimaginable loss of life and property across the globe. Bomber airplanes shadowed the sun, the earth groaned with unceasing explosions, while the oceans seethed with naval battles on a monstrous scale. Never before had the seven seas taken such hideous abuse, swallowing in their depths countless souls and scores of vessels. Among the latter were many splendid ocean liners, icons of a golden age, sent to the bottom by hostile submarines, in what we can only call humanitarian disasters.

1. RMS Lusitania

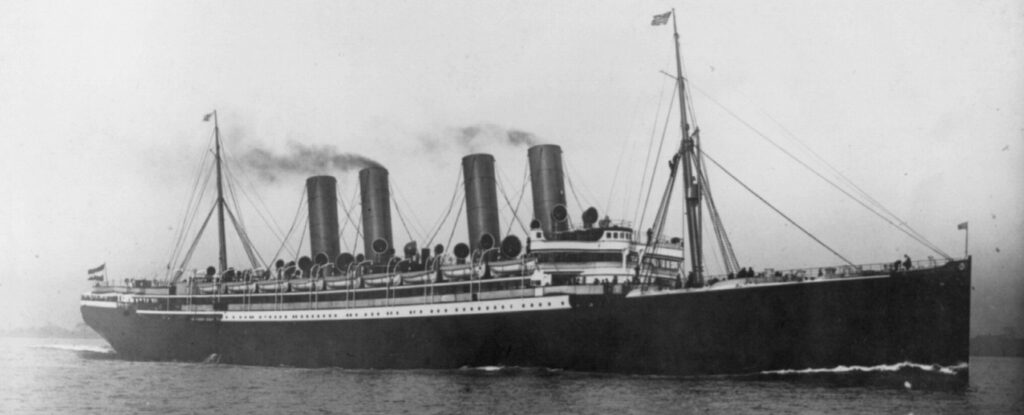

By the turn of the 20th century, German-British naval rivalry was spilling over to the merchant marine. Powered by national pride and soaring ambition, the recently unified German nation produced some of the most advanced liners of the time, sending transatlantic pioneers like Cunard back to the drawing board. In 1897, the Vulcan shipyards launched the largest and fastest steamship the world had ever seen. Just short of 200 meters in length, the 14,000-ton SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was not only the first ever four-stacker, but her class snatched and held the Blue Riband for ten consecutive years. In the intense competition for European immigrants flocking to the New World, British lines could not afford to pass.

In 1903, Cunard approached the British Navy with a mutually beneficial proposal – the Admiralty would finance the construction of two megaships to trump the Germans, as well as to expand the Navy’s capacity of auxiliary cruisers in case of war. The new liners, while remaining commercially competitive in passenger shipping, would also follow Admiralty specifications for eventual wartime conversion. Hands were shaken, and construction at the John Brown shipyard began the following summer.

Boasting four stacks and four turbines, the Lusitania made other girls in town look homely. Built with high-tensile steel and powered by a novel turbine engine, she was longer, faster, and tougher than any other vessel on the ocean. And if this was not enough to make the competition green with envy, the Lusitania had extensive electric lighting, a wireless telegraph, electric elevators, and a proto-air-conditioning system with steam-driven heat exchangers. She and her sister Mauretania kept the Blue Riband safe in Cunard’s possession for the next 22 years.

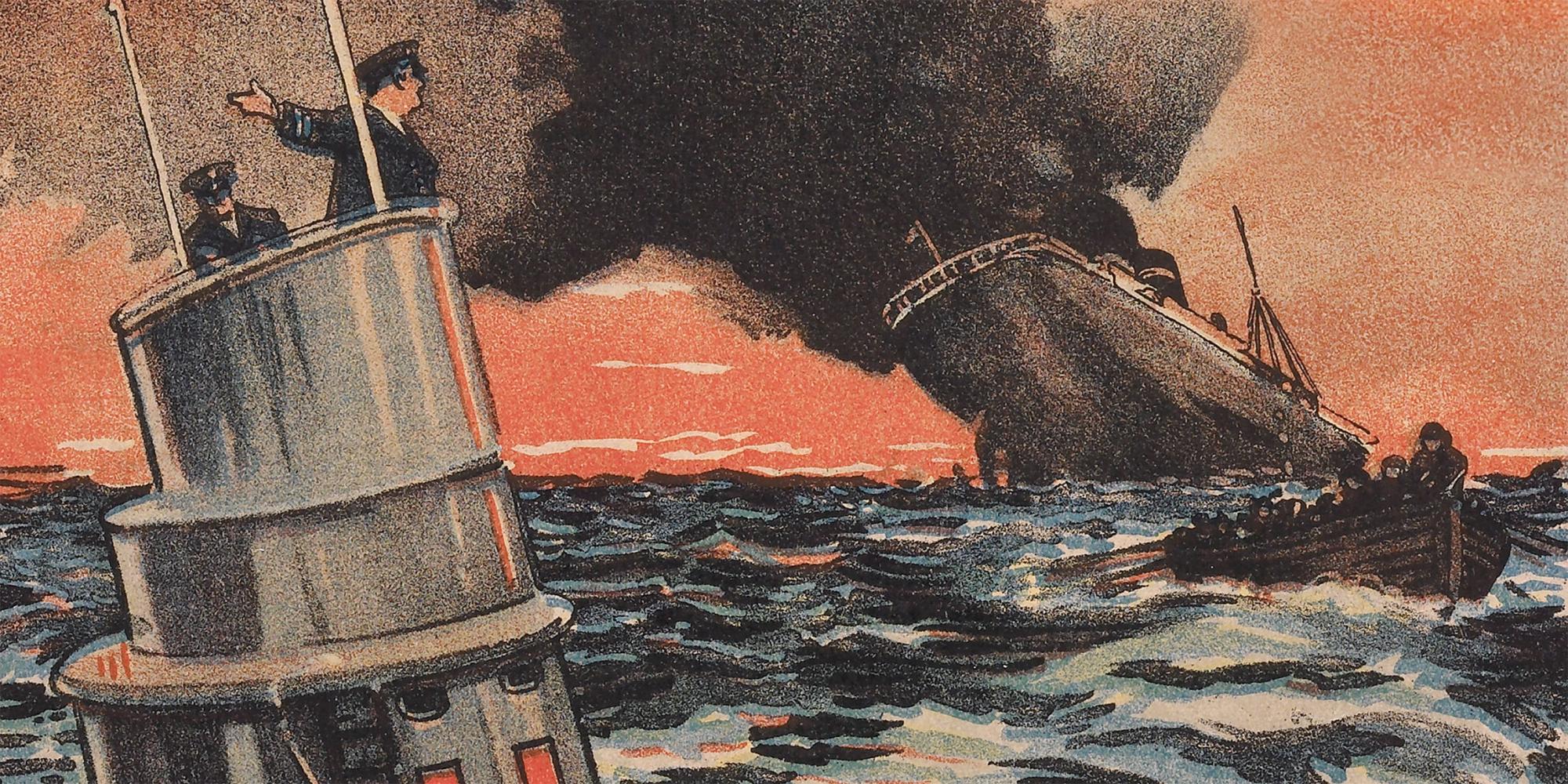

With the eruption of hostilities in 1914, dropping passenger numbers and the danger of mines sent many liners on an involuntary sabbatical, but Lusitania stayed on the Atlantic as an auxiliary ship. With the appearance of U-boats off the British coast, however, the rules of the game changed overnight, and the Lusitania’s instantly recognizable profile became a liability. Ignoring German warnings to curb civilian travel, the celebrated Cunarder left New York on 1 May 1915 for the last time. Six days later, off the southern coast of Ireland, the Kriegsmarine’s U-20 submarine spotted the imposing silhouette. One torpedo was all it took to send the magnificent Lusitania to the bottom, drowning 1,197 people.

Looking for ocean liner collectables? Visit the The Shipyard Shop!

2. MV Wilhelm Gustloff

The 25,000-ton diesel-powered giant made her debut in 1938 as a Nazi cruise ship, only to be requisitioned by the Kriegsmarine at the start of WWII a year later. While still in construction at the Blohm & Voss shipyards, the Nazi tour operator Kraft durch Freude boasted its intention to name her after Adolf Hitler, but following Swiss Nazi leader Wilhelm Gustloff’s assassination, the Fuhrer himself weighed in to change the name.

Although brief, her civilian career was dynamic, including a nerve-racking rescue of the entire crew of British collier Pegaway amid a violent storm in April 1938, as well as a bizarre spell at Tilbury a few days later. There, safely anchored in international waters, she served as a polling station for Germans and Austrians in Britain to cast their vote in the Anschluss referendum. Even more curiously, all these events took place before the official maiden voyage of the ship to the island of Madeira. The most memorable event on that leisurely trip was the sudden death of the Gustloff’s captain.

The following year, while still in civilian colors, the vessel transported the victorious Condor Legion from Spain, now firmly in the hands of General Franco. The most harrowing success of that notorious Wehrmacht unit had been the bombing of Guernica, later depicted in Picasso’s unsettling work of the same name.

In the grisly spirit of the war, the sinking of MV Wilhelm Gustloff remains the deadliest maritime disaster in history. In the closing chapters of the war, she was part of Operation Hannibal, a mass-evacuation of German soldiers and civilians from East Prussia, in anticipation of a Red Army offensive. Wilhelm Gustloff left Gdynia on 30 January 1945, heading for deep water. To avoid collision with other German vessels, Captain Petersen even took the risk of turning on the navigation lights, making an easy target of the enormous liner. It was a lucky day for Soviet submarine S-13 and a nightmare for the nearly 11,000 on board the Gustloff. The Soviets fired three torpedoes, sinking the ship in less than 40 minutes with 9,600 fatalities, among them many women and children.

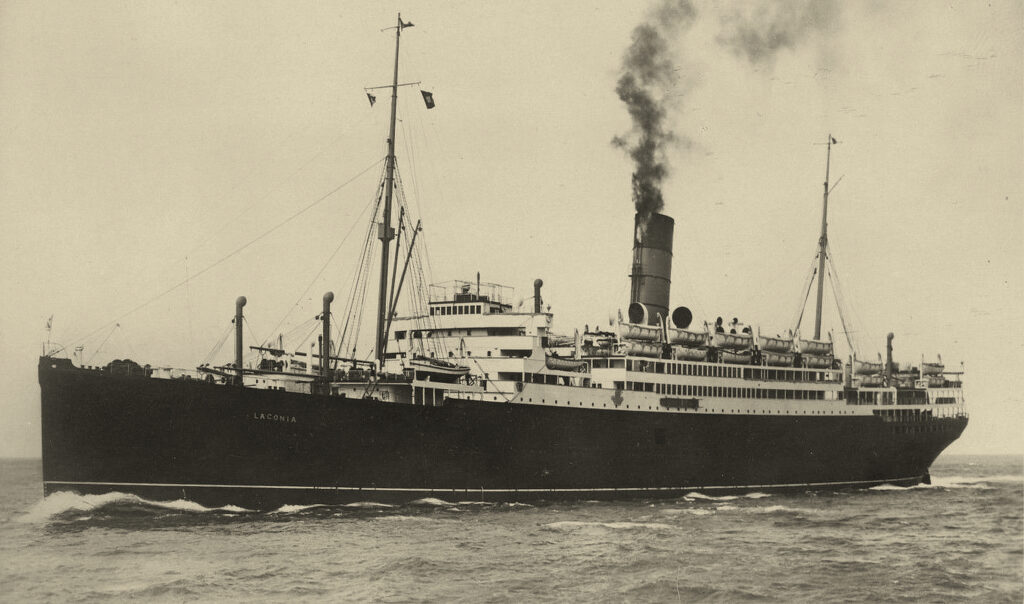

3. RMS Laconia

The Second World War claimed another distinguished Cunarder, credited with the first world cruise in history. Although of unassuming size, compared to the giants of the era, the Laconia offered the flexibility required by a changing world. While plying the Transatlantic line in the warmer months, she operated as a cruise ship in winter, in fierce competition with Cunard’s German rivals. Famously, she was chartered to the American Express Company for a round-the-world trip in 1922, stopping at 22 ports in 130 days. And just like today, the dream voyage must have come with a hefty price tag, as it only attracted 347 tourists.

When WWII flung the world into a chaos of destruction, the British Navy requisitioned the RMS Laconia, turning her exotic, palm-decorated salons into cargo holds and living quarters for soldiers and prisoners of war. Armed with heavy field guns and loaded with gold bullion for the war effort, she steamed off into the submarine-infested Atlantic.

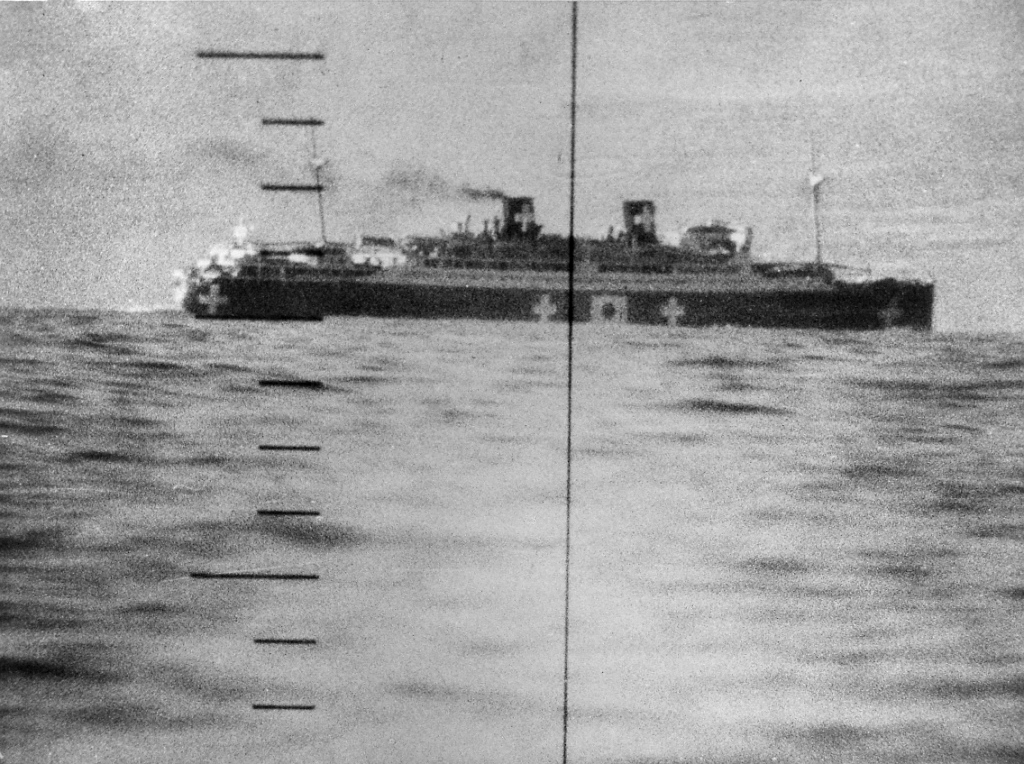

The infamous Laconia Affair began on 12 September 1942, when German submarine U-156 spotted the former liner not far from the remote island of Ascension in the South Atlantic. Unaware that Laconia carried 1,800 Italian prisoners of war, Captain Hartenstein ordered fire, and a few moments later, the vessel shuddered with the explosion of a direct hit. Women and children were evacuated almost immediately, while the Polish guards locked up many POWs in the holds, shooting those trying to escape.

Captain Hartenstein of the U-156, now shocked by the scene of civilians and POWs in the water, shark fins circling around them, began a hasty rescue operation under a Red Cross flag. Ordered by Admiral Dönitz of the Kriegsmarine, several other U-boats in the vicinity rushed in to help.

Predictably infuriated, for the submarines were on their way to a clandestine attack on Cape Town, Adolf Hitler ordered immediate abandonment of the rescue operation, dispatching instead a combined force of German, Italian, and Vichy-French vessels. By that time, the U-156 was bursting with more than 200 rescued men and women. The captain, sensing that help was nowhere near, broadcasted a message in English to all nearby vessels, asking for assistance and guaranteeing not to attack them. The British, worried that the message might be a trap, did nothing. The U-156 spent the next three days and nights rescuing survivors, until two other German U-boats and an Italian submarine arrived to lend a hand in the operation. A bizarre caravan of four submarines, lifeboats in tow and decks packed with survivors, made way for Africa.

What followed was a quagmire of miscommunication. An American bomber spotted the U-156 with Red Cross markings and alerted the nearby Allied airbase on Ascension. The officer on duty, for reasons that remain controversial to the present day, ordered attack. The aircraft dropped several bombs and depth charges, missing the U-boat but killing dozens in the lifeboats. Hartenstein cut off the lifeboats and after warning the people on deck, made a slow submersion to allow enough time for safe evacuation. One lifeboat made it to Africa, while another ran into a British fishing boat, both cases sustaining severe casualties in the open sea. Despite the efforts of the Axis fleet in the South Atlantic, 1,658 perished in the incident, most of them Italian POWs.

4. MS Tatsuta Maru

Japan lost countless ocean liners to submarines, with a staggering number of casualties. The empire’s explosive offensive in WWII took colonial powers by surprise, their navies and air forces scrambling for a relentless hunt in the Pacific.

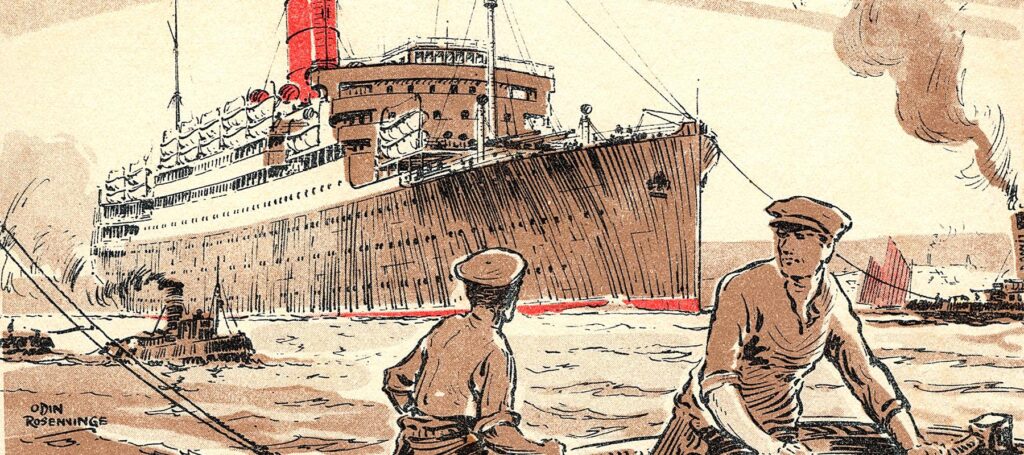

Tatsuta Maru was a child of the new era – a sleek, diesel-powered beauty, built in 1930 by the Mitsubishi shipyards in Nagasaki for regular transpacific service to San Francisco. Despite her modern silhouette, her interiors offered to passengers all the classical elegance expected from a liner of that age. Beneath the resplendent salons hummed four Mitsubishi-Sulzer diesel engines, powering the quadruple screws to a breezy cruising speed of 21 knots.

The troubled times produced plenty of distinguished celebrities and downcast refugees, and the compact Japanese vessel carried both. In the turbulent days leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Tatsuta Maru happened to carry the last oil exported from the US to Japan, albeit barely enough to return home. A few months later, she also became the last Japanese civilian passenger vessel to leave the United States.

Later that year, the Empire of Japan devastated the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, and Tatsuta Maru reported on duty as a troopship in the world’s third largest navy. She sank in a gale, some 150 miles from Tokyo, struck by four torpedoes from the Porpoise-class USS Tarpon. None of the 1,400 on board survived. Sadly, this was only the beginning.

The Shipyard