In Part 1 we saw the early outbursts of inspiration and genius, which led to random but fascinating developments – the maritime equivalent of Woodstock, in a way. But just like the hippie storm matured into the Golden Age of classic rock, so did the pioneering submarines of the 1860s’ and 1870s’ help establish a mainstream element of 20th century naval strategy. And to exploit our musical analogy to the maximum, the Led Zeppelin of 19th century submarines was a hot-blooded Irishman, whose design conquered the world in more than one way.

John Philip Holland: The Prometheus of Submarines

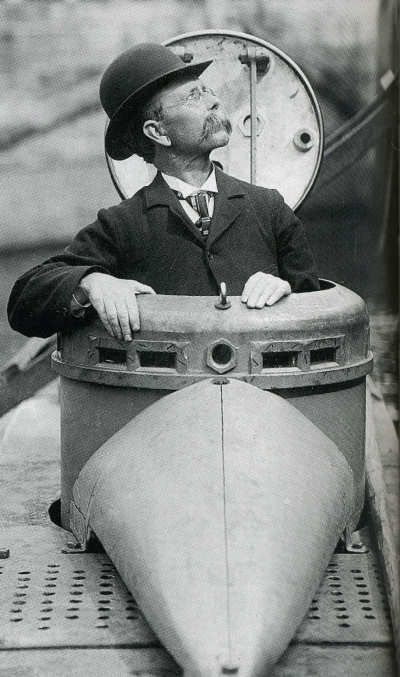

We have all heard about proverbial accidents changing the course of history, like the apple that fell on Newton’s head. In the case of submarines, the hero was John Philip Holland, and the apple was an icy street in Boston, where the newly arrived Irishman slipped and broke his leg. And since broken legs take plenty of time to heal, Holland filled the endless days with refining his ground-breaking submarine designs.

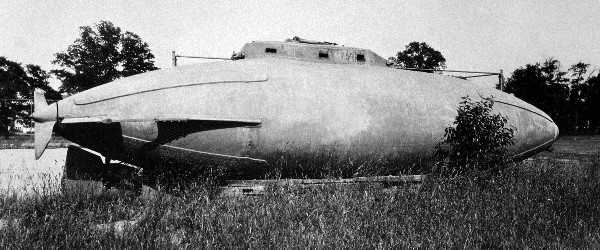

It was more of a passionate hobby at the time – the US Navy kept ignoring his submissions as flights of fancy, leaving the Fenian Brotherhood (a secret Irish secessionist organization) as his only paying customer. But the fruit of this mutual affection was stillborn – after building the Fenian Ram submarine for the Brotherhood, the friendship began to sour, with the temperamental Holland refusing to train the revolutionaries how to operate the vessel. The Fenian Ram was left to rot in a New Haven shed. Thankfully, it was eventually purchased by the Paterson Museum in New Jersey, where it brings joy to our hearts to the present day.

The great man’s first real opportunity came in 1896, when he won a tender with the US Navy Department, establishing the John Holland Torpedo Boat Company. After heavy interference on behalf of naval experts, the first submarine turned out, as Holland himself put it, “over-engineered”. The project was scrapped. The Irishman’s sixth design proved to be the lucky one, and on October 12th, 1900, The US Navy commissioned it first official submarine – the USS Holland (SS-1). The first one to use combined gasoline-electric propulsion, it boasted several innovative features like a conning tower, ballast and trim tanks, as well as a dynamite gun.

In the years that followed, John Philip Holland’s ventures expanded globally. His company supplied five submarines to the Empire of Japan, which at that time was wiping the floor with the Tsar’s Pacific fleets. And, to the outrage of his former Fenian friends, the Irish inventor sold no less than three designs to the British Royal Navy for their pioneering Holland-class.

Holland did not live to see his inventions’ true baptism of fire – the great visionary died in August 1914, only two weeks after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and sparked the global massacre that we know as the Great War.

A Hero’s Death in Japan

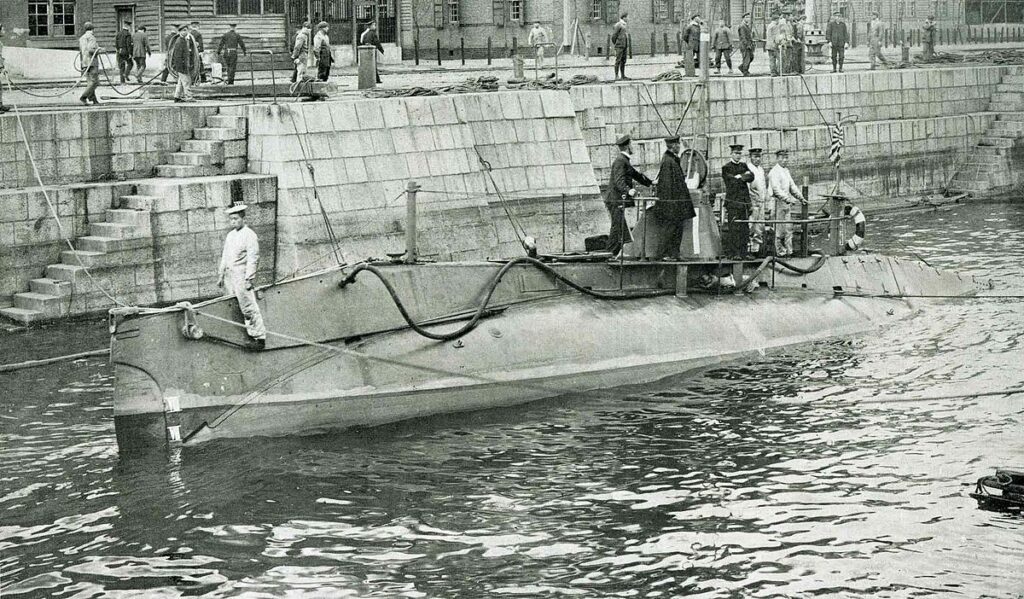

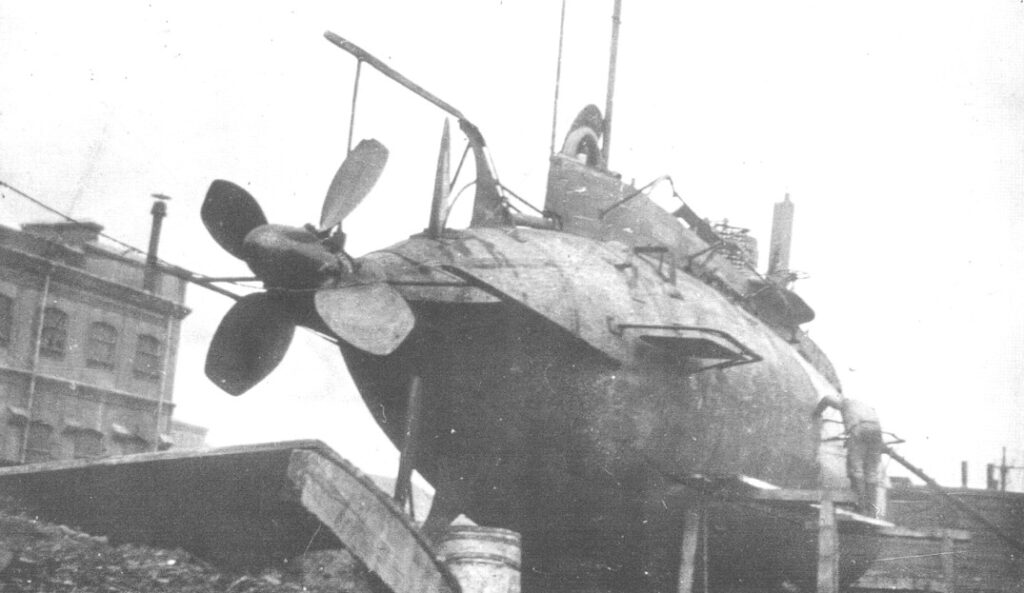

The five boats that Holland sold to Japan in 1905 arrived too late to see any action in the Russo-Japanese War, but Tokyo was nevertheless determined to explore this new weapon of naval warfare. As a rising industrial powerhouse, the Japanese Empire quickly adopted the technology by purchasing blueprints from Holland and starting their own production at the Kawasaki Dockyard in Kobe. 1906 saw the completion of the Kaigun Holland #6, a longer and more powerful modification of the five imported submarines, with an impressive 300 hp gasoline engine, ensuring cruising ranges of up to 340 km at 8 knots. The electric motors provided enough energy for dives up to 22 km.

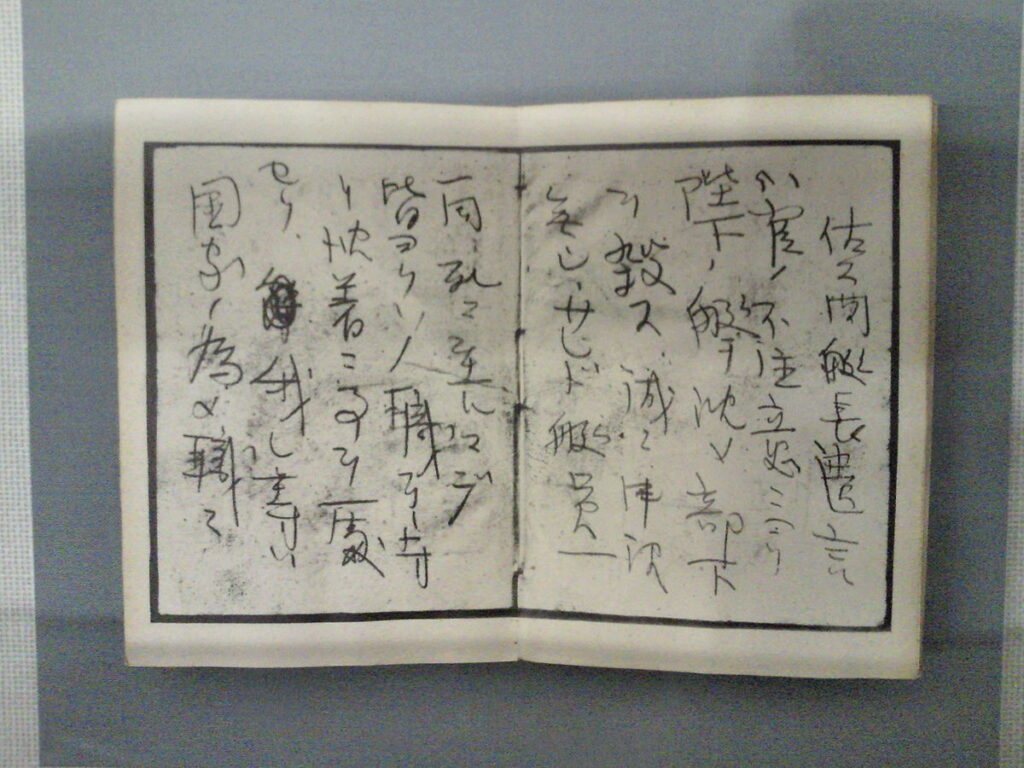

Perhaps the most unusual and emotional chapter in the boat’s brief history was its sinking in 1910. During a training dive off the coast of Hiroshima, a sluice valve malfunctioned, flooding the rear and sinking the boat stern-first. As Lieutenant Tsutomu Sakuma and his crew understood the end was near, the commander sat down under the dim light of the conning tower and wrote a detailed report on the nature of the malfunction, as well as the measures undertaken to resolve it. Suffocating with gasoline vapors, Sakuma ended his account with a letter of apology to Emperor Meiji for losing the Kaigun and its men, ascertaining the crew’s honorable behavior in the face of death and pleading that Japan continue its submarine program despite initial failure.

Shortly before losing consciousness, Sakuma scribbled down a farewell to his father, so discreet that the thunderous emotions of a dying man are only detectable between the lines. When the submarine was found and recovered, the crew were still at their places, as if frozen on duty for eternity. The nation (deservedly) praised them as heroes, and Commander Sakuma’s journal was preserved for future generations as a symbol of courage.

Dive in Russia, Emerge in the USSR

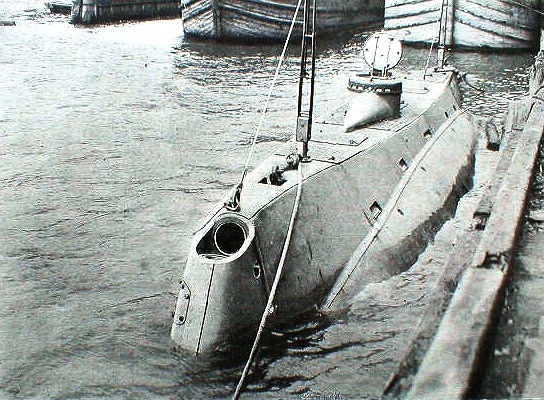

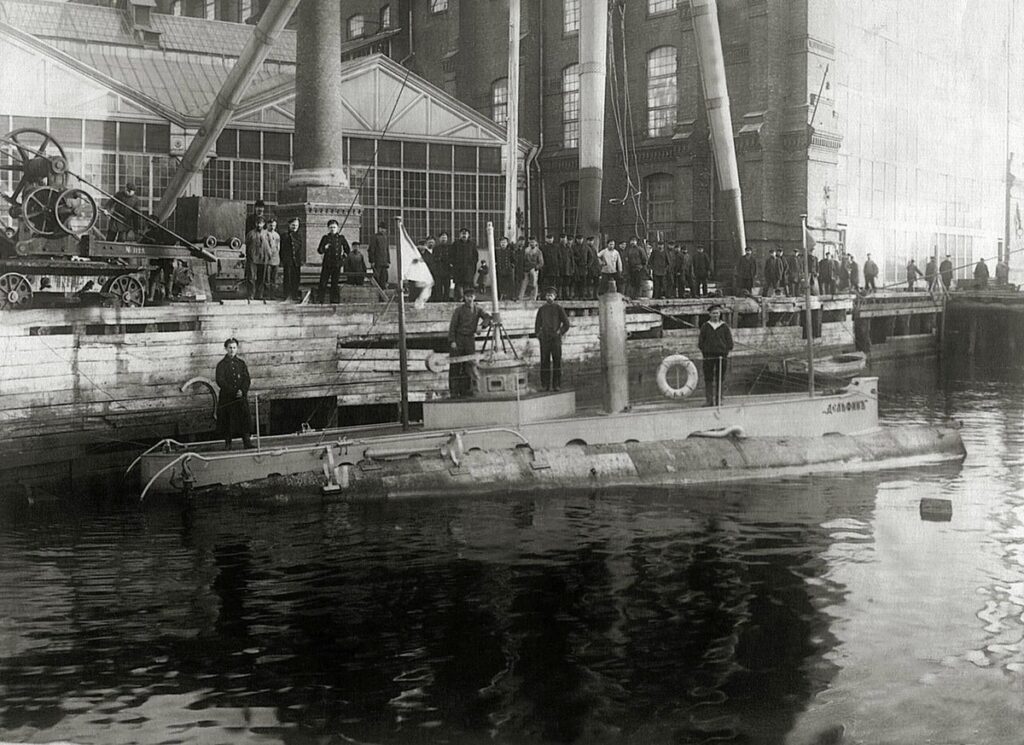

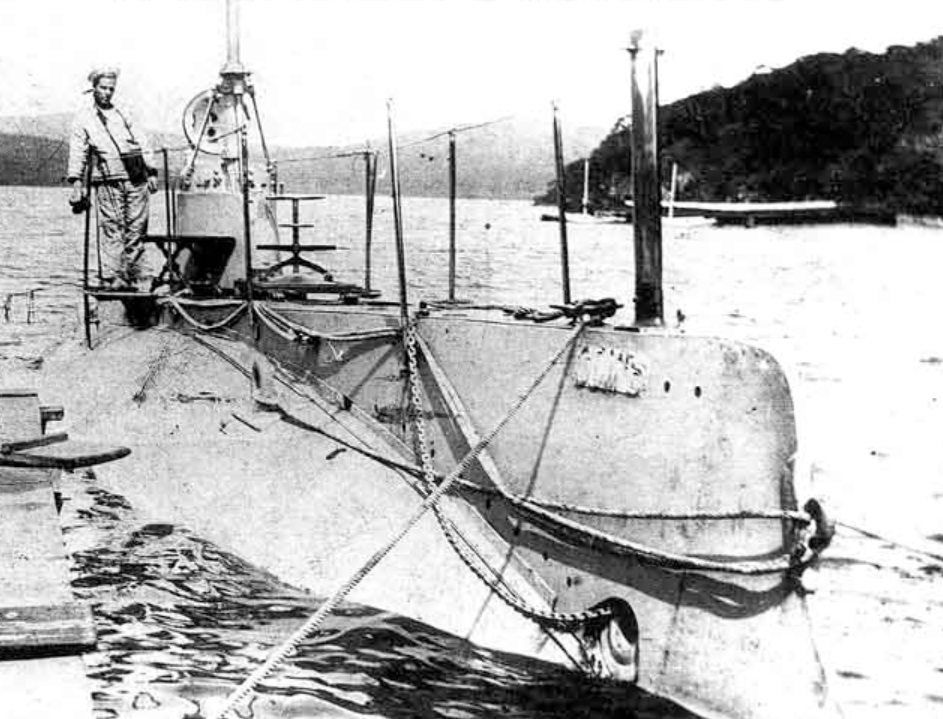

In war, timing is just as crucial as courage, and early submarines often missed the moment. Delfin (also known as Torpedo Boat 150) was the first U-boat of the Russian Navy, launched in 1902. The peak of its illustrious career were two record-breaking journeys halfway around the world…over land. Here is how it all happened.

Project “Torpedo Boat 113” began in 1900 in St. Petersburg, where an elite team of naval engineers studied various Western designs and propulsion technologies. It was the first small step in one of the most successful submarine programs in history. And “small” is the keyword here. The engineers had orders from the top to make the boat as compact and as cost-effective as possible – no surprise, considering how many prototypes sank before seeing any action. And with diesel engines of the time being somewhat clunky, the final configuration for Torpedo Boat 113 was a Daimler gasoline engine, with a Sauternes-Garlet electric motor and an Elwell et Leytrig air-compressor. Finally, two external Whitehead torpedoes in Drzewiecki drop-collars made the vessel as lethal as they came.

In 1901, with construction half-finished, the chief electrician of the project visited the Holland Shipyard in the USA, where he was allowed to board a submarine for a test-dive, gathering valuable know-how from the global leader. This led to some changes in the Russian design before the boat finally received commission in 1902 as Torpedo Boat 150.

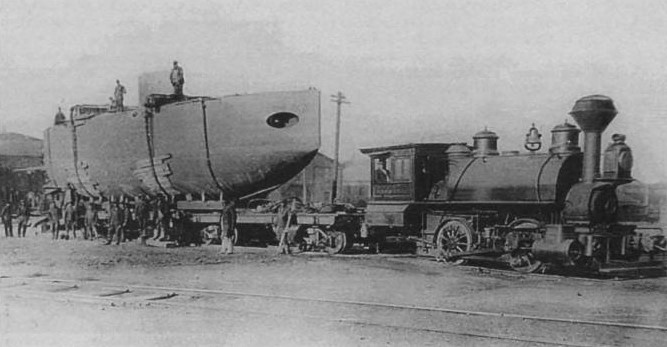

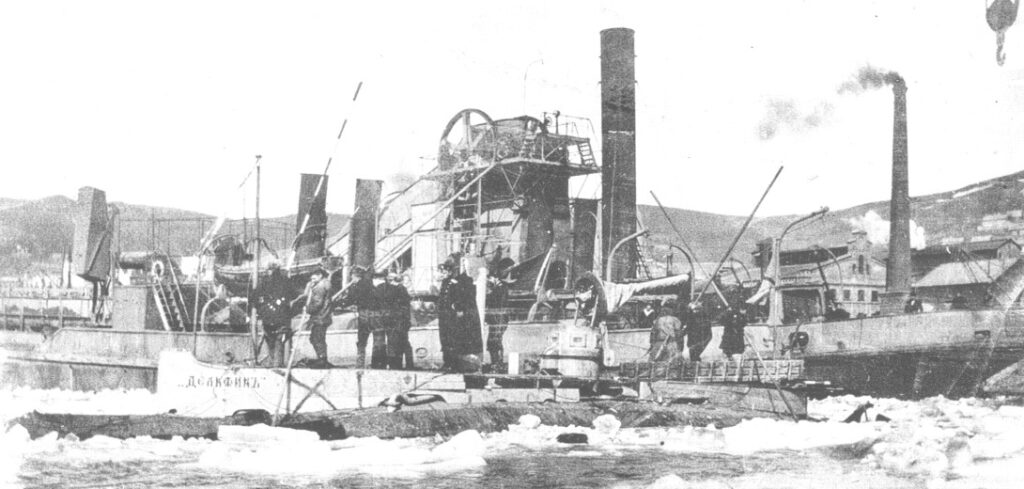

With the onset of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, the Imperial Navy renamed it Delfin, but the new name failed to bring good fortune to the poor vessel, which sunk in St. Petersburg just two weeks later, killing 24 of the 36 men on board. After a few months at a St. Petersburg shipyard, the repaired Delfin was loaded on a train for a trans-Siberian journey to Vladivostok, where it joined the Som (a Holland-class submarine) and Kasatka (a Russian-built upgrade of the Delfin) to fight the Japanese in the North Pacific.

But as is the case with many early submarines, the Delfin was more deadly to the crew than the enemy. Before it could engage in battle, the boat suffered a series of explosions from fuel vapors, and the major repairs lasted well after the end of the war. The next opportunity for battle glory came some nine years later in World War I, but another explosion in 1914 drove the final nail in the Delfin’s coffin.

Once again, it found itself strapped onto a train, this time in the opposite direction. In a Vologda dockyard, it was converted to a barge and towed to its retirement destination – Murmansk. But, with the new Bolshevik regime unwilling to maintain obsolete equipment, its Arctic service was brief. The first Russian submarine spent its last years lying on a beach, before being scrapped in 1920. And although the Delfin itself had a dull and painful career, it was the first milestone in a glorious naval success-story, which outlived both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

His Majesty Arrives Late

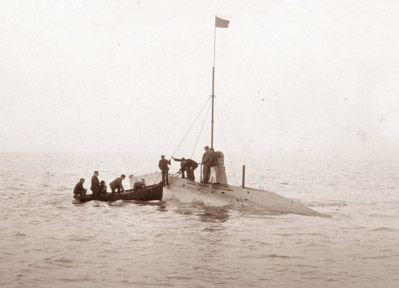

Despite its naval superiority at the time, or perhaps because of it, the British were in no hurry to adopt this novel and unestablished technology. Unconvinced in the potential, the Royal Navy preferred to wait and observe.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the Admiralty decided that these small underwater capsules could indeed threaten British vessels in case of war, not to mention their defense capabilities when positioned around key ports. This eventually led to the secret commissioning of a modest submarine from the Holland Company. So secret, in fact, that they labeled the dock building as “yacht shed” and decided against a launching ceremony, when the Holland 1 was completed in 1901. And even though John Holland provided a team of experienced submariners to train Royal Navy personnel, the British continued to dislike the boat for its complicated operation.

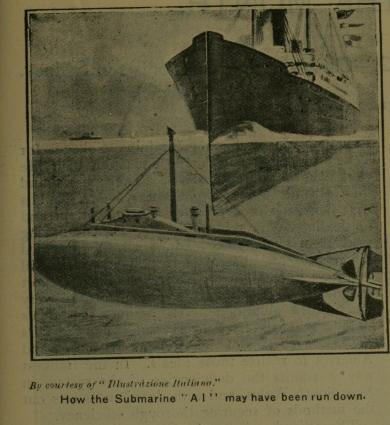

Still, the Holland 1 and its class were successful enough for the Navy to commission a proprietary British design in 1902 – the A1. Built by Vickers in Northwest England, the new class boasted a double propulsion system – electric motors when submerged and petrol engines when on the surface. The last one, the A13, even tested a diesel engine, without success. Over the next two decades, the A-class proved notoriously accident-prone, often due to technical problems.

The first curious deployment of this nascent submarine fleet was in the 1904 Dogger Bank incident, when Russia’s Baltic Fleet took some British fishing trawlers for Japanese torpedo boats. In the resulting chaos, the Russians sunk one boat, killing two fishermen and injuring several others. To complete the mayhem, the Tsar’s people also fired on one another, resulting in the deaths of a sailor and an Orthodox priest on board the legendary cruiser Aurora.

With Russo-British relations at their usual low at the time, the Royal Navy ordered 28 battleships and several Holland and A-class submarines to prepare for action. Thankfully, both sides settled for a diplomatic resolution before the conflict could escalate.

The Dutch Like to Stay Afloat

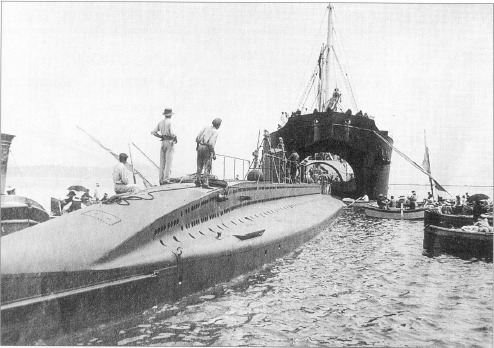

A great naval power at the time, the Dutch took even longer to take the plunge. It was again John Holland who changed their mind, this time with a Holland 7P type, built in Vlissingen in 1905. For the American company, the project was a bit of a gamble, as the Royal Netherlands Navy wanted to test the boat first and then decide whether to buy it. After an entire year of trials, the Dutch finally signed the check and commissioned the boat as HNLMS Onderzeese Boot 1 (Undersea Boat 1).

As the Netherlands remained neutral in the Great War, the O1 saw little action but proved an asset for the training of the country’s first generation of submariners. In 1914, her Otto petrol engine was replaced with a more powerful MAN diesel motor.

Germany – A Change of Heart

Nothing symbolizes the German war machine better than tanks and U-boats, and while tanks had to wait until the Second World War to shine, U-boats joined the Kriegsmarine just in time for the first.

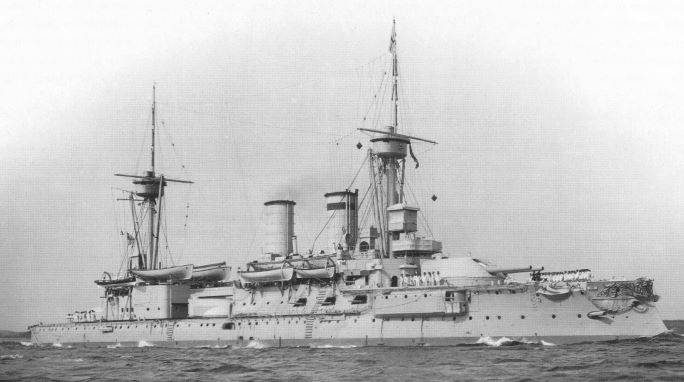

But things didn’t look promising at the turn of the century, for the Imperial Naval Office in Berlin was headed by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, whose ambitions flew in a different direction. Despite a brilliant early career as a torpedo engineer, as an admiral Tirpitz dreamt of a conventional high-seas fleet that could rival the British on their home turf. For a long time, he dismissed submarines as a weapon of the weak, and his grandiose and somewhat romantic vision were well-taken by Kaiser Wilhelm II. For many years, underwater warfare remained out of the conversation at Berlin Palace.

This changed in 1905, when industrial giant Krupp convinced the Kaiserliche Marine to begrudgingly commission its first submarine, the U-1. Already a supplier of Karp-class submarines to the Russian Imperial Navy, Friedrich Krupp’s Germaniawerft got the contract, their Kiel dockyard completing the boat in 1906.

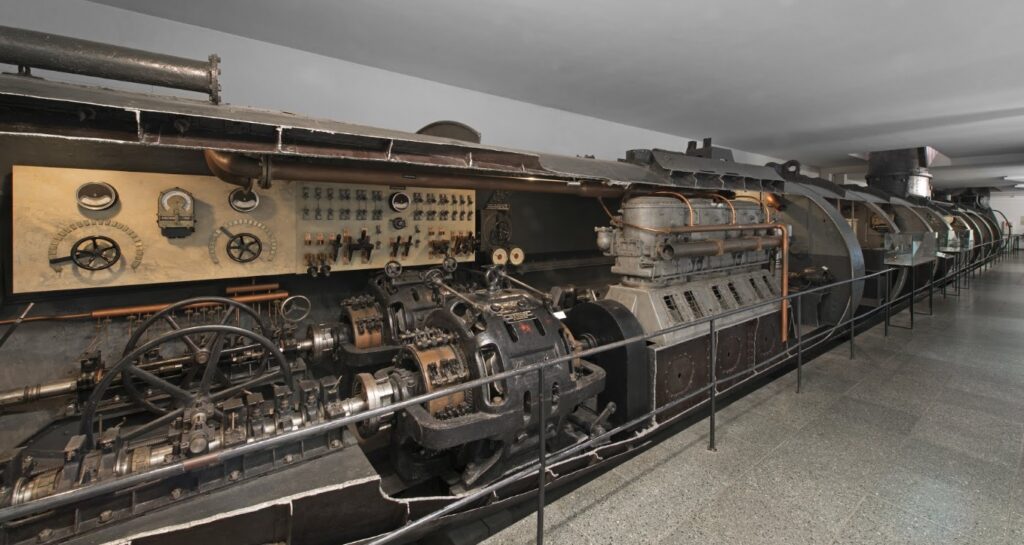

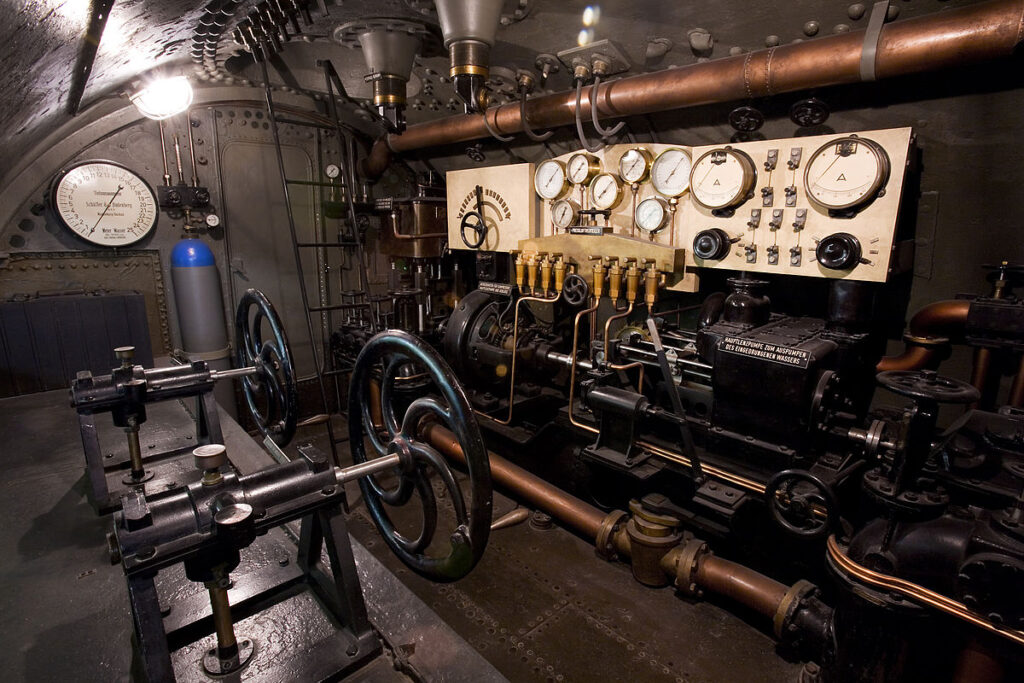

As it often happened at the time, the new acquisition was more of an experimental project than a weapon of war. A redesigned Karp-class, the U-1 tested one of the first usable gyrocompasses – a huge step forward in underwater navigation. The German engineers also decided against the popular but hazardous gasoline engine, choosing instead a kerosene motor with an electric starter. The move led to mixed results, with kerosene engines proving inefficient and cumbersome to operate.

Soon made obsolete by superior diesel-powered vessels, the boat never saw action beyond training. In 1919, the modest pioneer U-1 found a new home at the Deutsches Museum in Munich, where it can be seen and admired until the present day.

A hesitant step itself, the U-1 set the German Navy on a course toward global subsea domination in the following decades. What the admirals strove for with towering battleships, the engineers achieved with tiny U-boats. The Germaniawerft alone built and delivered 84 submarines, including the legendary U-35, U-47, and U-96.

Want to read more about German submarines? I highly recommend Dominic Etzold’s Reaping the Whirlwind. Click image below to have a closer look!

The Girl from Ipanema

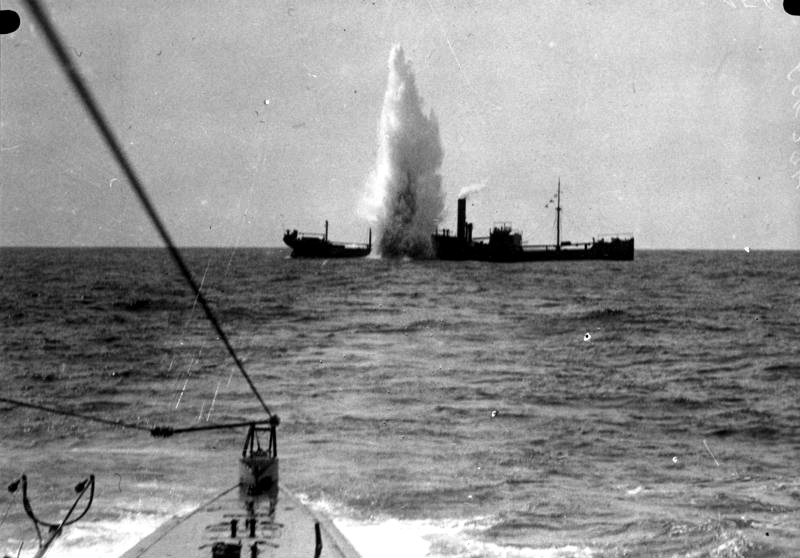

Brazil’s first submarine was not only technically capable, but it also arrived in style. Built in 1913 in La Spezia, the F1 arrived in Rio from its transatlantic journey on board the SS Kanguroo – a heavy-lift French steamship, specially made to carry submarines. With her design similar to a floating dry dock, the Kanguroo was a masterpiece in her own right, even though she took weeks to load and unload each time.

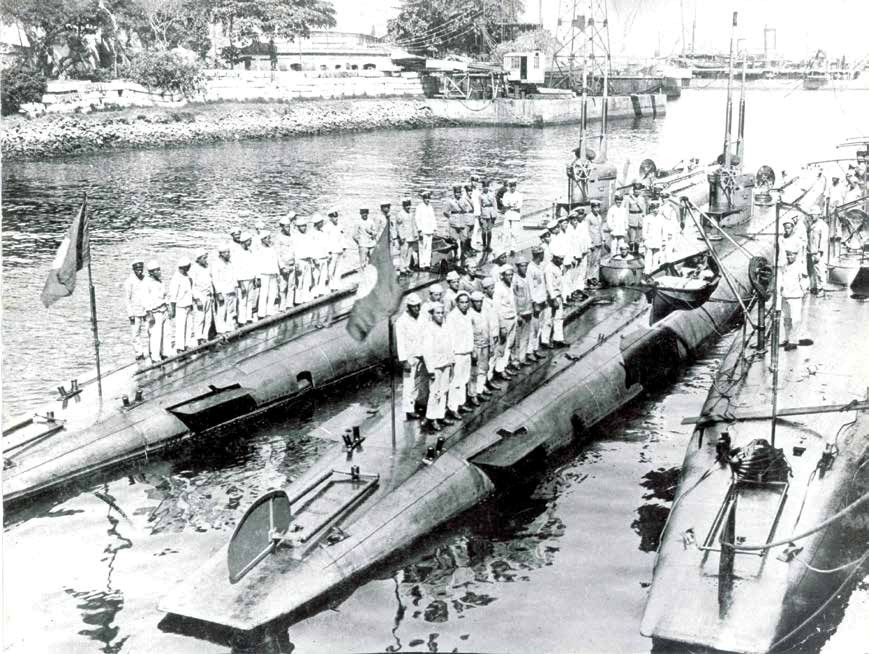

A few years before, the Brazilian leadership was nearing the conclusion that competing against the navies of great powers was not only technically challenging, but also financially unrealistic. The admirals in Rio de Janeiro quickly identified the potential of submarines as a cost-efficient defense weapon, resulting in the commissioning of three submarines to the Italian shipyard Cantieri Navale FIAT-San Giorgio.

The three boats of the Foci-class (F1, F3, and F5) were relatively large at 45 meters length and displaced 250 tons. They belonged to a recent wave of mighty diesel-electric submarines, equipped with two FIAT six-cylinder engines of 325hp each, plus two electric motors of 260hp. With this powerhouse on board, the F1 achieved an impressive cruising range of 1,600 nautical miles, and 100 miles when submerged. And to keep the submarines busy on such long cruises, the large size allowed room for four Whitehead torpedoes. Other novel equipment included two periscopes (introduced only three years earlier in England) and a wireless telegraph.

When Brazil declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the F-class submarines were deployed to patrol the coastline around Rio de Janeiro. After the Great War ended in 1918, the three sisters continued their service as training vessels, all the way until their decommissioning in 1933, which was marked with an emotional naval parade.

On the Power of Dreams

Although this has been little more than a birds-eye overview, the early history of submarines confirms something that few of us dare to believe – big dreams can come true, albeit at very small steps. Born as a spark in someone’s imagination, the modest 19th century sub overcame numerous technical, administrative, and historic hurdles to earn the title of top predator beneath the ocean waves. Nowadays, with advanced nuclear and communication technologies, few of us can imagine the global balance of power without the silent presence of the submarine.

The Shipyard