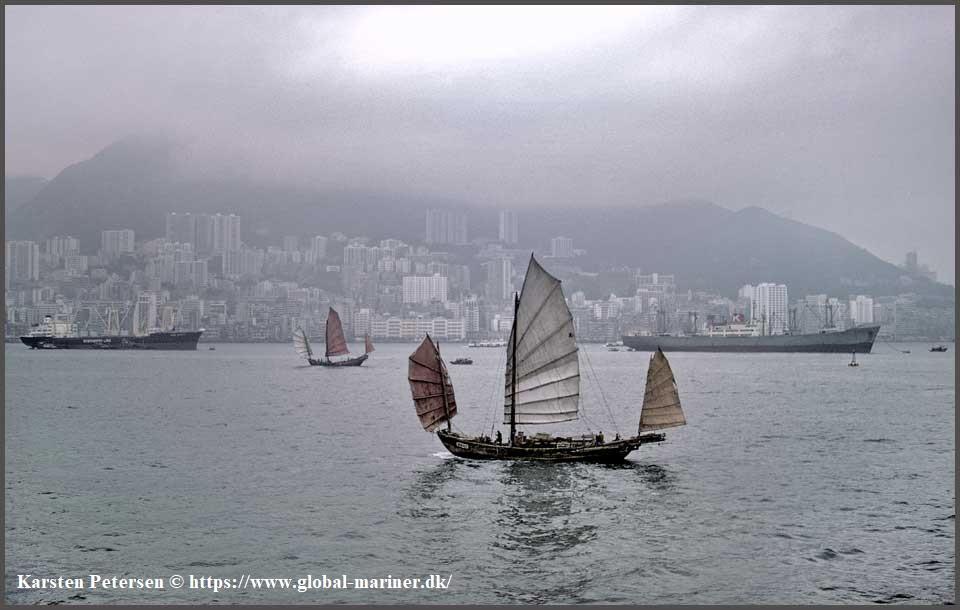

Despite a turbulent past, challenging present, and uncertain future, Hong Kong remains one of the most captivating and loved port cities in the world. And while the fashion nowadays is to extoll its colonial glory-days and despair over its Communist future, the ‘Fragrant Harbor’ is and will remain more than a gambling chip in the game of global politics. In this series, we dock at the Port of Hong Kong, delving deep beneath the glittering surface to reveal the maritime roots of this great Asian metropolis.

The Dragon’s Rumbling Belly: Pre-Colonial Hong Kong

A popular remark among British empire-builders was that Hong Kong used to be barren and irrelevant before 1841. However, long before Queen Victoria added the tiny island to her endless list of dominions, the area was already buzzing with maritime activity. A thousand years before Christ, even before the arrival of the Chinese, the Baiyue tribes had already established themselves as a regional naval power. Rowdy, athletic, and heavily tattooed, they were able seamen, master shipbuilders, and skillful swordsmen.

Avoiding their northern Han neighbors, they explored maritime routes along the coast, reaching the tropical communities of Southeast Asia. A lack of Han maps from the period was thought to imply that the lack of interest was mutual, but modern archeologists have discovered several Han Dynasty tombs in Kowloon, as well as graves dating from the Sixteen Kingdoms (4th century AD) on Lantau, Pak Mong, and Lamma Island. Some historians see this as a sign that by that time, the Baiyue were already being assimilated into the increasingly dominant Chinese ethnicity.

The first wave of maritime development in the Pearl River Delta took place under the Tang Dynasty. With the establishment of Guangzhou as a commercial center in the 1st century AD, Hong Kong’s location in the deeper channel of the river boosted the island’s strategic importance. Later, as the Tang stretched their maritime routes to the Persian Gulf, the port of Tuen Mun became a valuable supply and repair hub for the merchant traffic. Proof of this are the lime kilns found in the vicinity, in which local craftsmen burned seashells to produce caulk for ship hulls.

A few centuries later, the Song Dynasty placed a customs checkpoint on the island, making it an important stopover in the Guangdong-Fujian trade with its vast quantities of rice, porcelain, and tea. The increased traffic (and profits) stimulated local enterprise, and by the end of the 10th century AD, local Kowloon residents had established themselves as significant producers of salt – one of the empire’s most treasured commodities.

Coastal trade became so lucrative that the Southern Song maintained a fleet of paddle-wheel ships, armed with canons and other firearms to defend the Pearl River Delta. But history has a dark sense of humor, and this cutting-edge navy ultimately proved useless. The deadly strike against the thriving Empire came not from the humid subtropical coasts, but from the windy steppes of the far North, from which Kublai Khan’s Mongol hordes stormed like a colossal blizzard.

The Dragon Turns on Itself

Great empires often become their own worst enemies, and Beijing’s policy in 1434 only confirmed this. Traumatized by a century of Mongol domination, the Ming Dynasty sealed the empire’s borders in an attempt to cut-off external threats and foster stability within. Somewhat ironically, this move spawned a lively smuggling hub on Hong Kong Island for the prized Jingdezhen ceramics. The success of the shady venture is evident by multiple discoveries of porcelain from the same period all over the globe – Portugal, Philippines, and Syria, to name a few. But such sporadic ripples in the south never reached the distant capital, and the largest kingdom in the world remained cloistered for two centuries.

Ming isolationism plagued China long after its abolishing. By the 17th century, inward-oriented policies had eroded the empire’s naval power to almost zero, and when the Qing came to the throne in 1644, rebuilding the navy was no longer feasible. Due to advanced deforestation under the Ming, timber was scarce, and logs had to be brought from overseas. With year-long delivery times from their southern neighbors, the Qing were forced to build mostly small, inefficient vessels. The result – China’s entire coastline remained undefended, constantly ravaged by pirates so out of control they even established their own customs offices. And with Hong Kong already versed in black-market practices, Cantonese privateers seized the opportunity.

In the first years of the 19th century, Lantau Island became the Nassau of the Far East – governed by pirates and largely autonomous from the monarch – but just like Nassau it did not survive long. By 1810, Qing sovereignty in the South was reaffirmed. To keep both pirates and the meddling Portuguese at bay, the authorities reinforced existing defenses with Tung Chung Fort, which still stands and is one of Hong Kong’s offbeat tourist attractions.

The Lion’s Challenge: Britain’s Arrival to China

When early British delegations anchored in the warm waters of Southern China at the end of the 17th century, they suffered a frosty reception. A Portuguese colony in Macao was already proving a nuisance for Beijing, and more well-armed European vessels at the poorly defended coastline was too much for the disdainful Qing court. But the British, lured by the enormous profits of the tea trade, did not wait to be invited. In the years that followed, the British East India Company (represented by a few somewhat disreputable individuals) built and nurtured a vigorous smuggling network. After several clandestine expeditions to map the marine passages of Guangdong and to assess their potential for trade and contraband, the scouting parties unanimously identified Tsim Sha Tsui as the best potential harbor in the area.

All ran smoothly, except one tiny hold-up: Britain could not afford its passion for tea. As the world’s leading manufacturer of goods, China showed no interest for European products, demanding silver as the only acceptable currency in its dealings with the West. And while the British Empire seemed to have an unquenchable thirst for tea, its coffers were running low on precious metal. Following several unsuccessful attempts to alter the terms of trade, the East India Company settled on a solution as simple as it was monstrous – to produce opium in India and smuggle it into China in exchange for silver. And with the Middle Kingdom proving to be a vast market for the drug, this move set the future of both empires for the next 150 years.

The Showdown: Opium Wars

Despite booming exports, the Qing gave exclusive trading rights to the city of Guangzhou and its top merchants (the Hong), a restriction that caused increasing irritation among foreign powers. The resentment was mutual, as China struggled with the catastrophic opium epidemic engulfing the population and eroding the Middle Kingdom’s social and political fabric. Tensions escalated to the point where the imperial authorities in Guangzhou raided foreign warehouses, confiscating opium stocks and expelling Western merchants to Macao.

One thing the Daoguang Emperor did not suspect, however, was how much political influence the opium cartels had in London. By the time Beijing realized its miscalculation, British steam-powered, iron-clad warships were already bombarding Guangzhou, while the pitiful remains of the Chinese fleet smoldered in the Pearl River. When the dismayed Qing court sued for peace in 1841, the price demanded by Britain included the small and unassuming island of Hong Kong.

But the new colony made a slow and shaking start, despite its freeport status. The First Opium War had forced several coastal cities to open for trade, and with Shanghai’s priceless access to the interior through the Yangtze River, Hong Kong had yet to finds its role in the big picture. The opportunity came in the 1850s, when a series of tumultuous events rocked China. The Second Opium War caused extensive damage in Guangzhou, while several rebellions engulfed Shanghai between 1853 and 1862, with Hong Kong suddenly emerging as the next best option for both foreign and local merchants. At the same time, the gold rushes in America and Australia devoured scores of Chinese laborers, with starving peasants streaming from the country’s impoverished rural regions to Hong Kong and Macao to board ships for San Francisco and New South Wales.

In the decades that followed, the legalization of opium in China and the booming ‘coolie’ trade fertilized numerous other businesses, establishing the young and controversial colony as a commercial hotspot. To unlock Hong Kong’s growth potential after the Opium Wars, London pressed China to cede Kowloon in 1860, securing both sides of Victoria Harbour. The colony’s size further expanded with a 99-year lease on the New Territories in 1898.

With the British position firmly established, Hong Kong entered the 20th century – an age of steam-powered liners, booming maritime commerce, oil, and war. An age as golden as it was turbulent. Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, in which the glorious and stormy events of the last century will be accompanied by stunning vintage photos of steamships, dockyards, and more!

The Shipyard