The rowdy sailor and his bottle of rum. Few stereotypes have stuck for so long, and this one is so deeply etched in our minds that even today’s standard of well-groomed, white-uniformed, and completely sober navy personnel has been unable to erase it from collective memory. Ships and drink go a long way – from the gallon of beer a day each sailor got in 1500s’ Britain, to the complete banning of alcohol in the 20th century. Looking at the uncompromising discipline and protocol that rule contemporary navies, it is hard to imagine that these same institutions invented what we now know (and enjoy) as cocktails, thus giving birth to modern drinking culture. Gin tonic, daiquiri, punch, and many other staple mixes were either invented, popularized, or inspired by the navy.

From this perspective, it would be easy to assume that our ancestors were a gang of rollicking degenerates, but as most things in history, there is more than meets the eye. So pour yourselves a tot and keep reading.

Alcohol in the Navy: A Match Made in Austerity

The European Renaissance, with its economic, social, and scientific developments, triggered a nautical race to the distant shores of Asia and the Americas. Whether for exploration, trade, or conquest, the challenges of this seafaring boom equaled its opportunities – crossing vast oceans required new approaches, not only in shipbuilding, but also in logistics and planning. Starvation, dehydration, scurvy, typhus, and tropical diseases plagued early transoceanic travel, and whereas none of these ailments is an issue on a modern ship, 16th century medical science was nearly helpless. Enter beer and wine.

Liquid Food

As always, we look at history in context. European appetite for maritime exploration was partially triggered by a phenomenon called the Little Ice Age – a gradual cooling of the climate between the 16th and the 19th century, resulting in shrinking crop harvests. Widespread food deficiencies made each calorie crucial, with beer and wine thus becoming vital staples. Alcohol was not only a substantial source of energy, with almost double the calories of carbohydrates, but the older fermentation processes left more residual sugar in the beverages, enhancing their nutritional value. Children made no exception from the bread-and-ale diet, although kids’ meals of the time came with weak beer or diluted wine.

But the key factor for alcohol’s prominent place on the sailor’s menu was the limited availability of drinking water on ships at sea. Often drawn from polluted sources and stored in unhygienic containers, water spoiled within a few days of embarkation, leading to mass dysentery and other digestive disasters. Wine and beer, thanks to the antimicrobial action of alcohol, hops, and fruit-acids, kept much longer and were safe to drink even when they soured.

But as fermentation is an ongoing process, the logistics got very complicated. In 1670 the French government had to issue detailed instructions to the navy about which wines to serve at different stages of the journey, based on how well each sort kept in various climatic zones. For this reason, white wines and those with low alcohol content were banned altogether, granting sailors a bottle of fine Burgundy a day. The problem of spoilage in tropical climates was solved later in the 17th century, when European navies gave preference to distilled liquor like rum, gin, and brandy.

Panacea

Another factor in favor of drinking on board was alcohol’s growing popularity as a medicine. Before you laugh, imagine that none of the products in your local pharmacy existed until the 19th and 20th centuries, with treatable diseases like scurvy, typhus, and malaria being a death sentence to any seaman unlucky enough to get them. Spirits were assigned countless anecdotal superpowers like countering scurvy, malaria, yellow fever, both constipation and diarrhea, rheumatism, and many other sailor’s scourges. Of course, medics were less enthusiastic than the crew, but few people at the time dared to stand between a sailor and his daily liquid comfort.

Carrot or Stick?

What cemented the daily booze ration, however, was the notion that it encouraged good behavior, since the threat of withdrawal discouraged mischief. Yes, you understood correctly – officers hooked their crews on liquor for more control. Dark, right?

Such ideas were especially popular among early strategists like Cardinal Richelieu, considered by many as the founding father of the French Navy. He famously stated his preference for sailors with saltwater and wine in their veins to the powdered and wigged aristocracy in Paris. This sentiment was echoed across the English Channel, where beer, wine, and brandy were believed to boost courage and stamina in the endless military campaigns of the time.

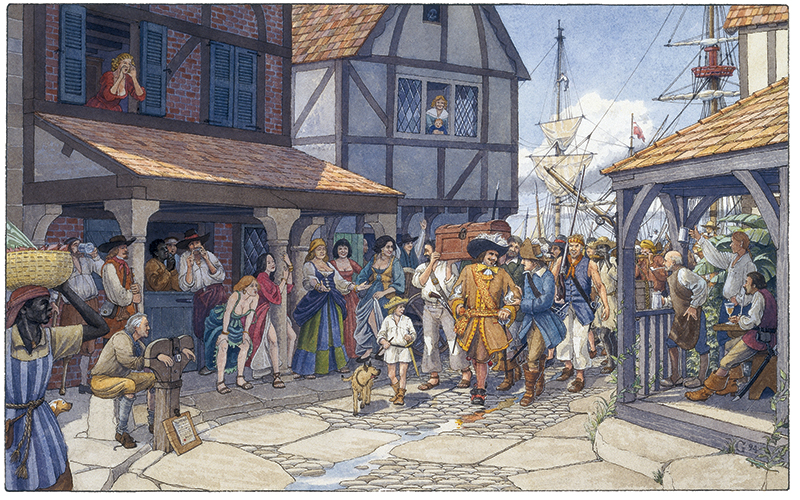

Yo, Ho, Ho, and a Bottle of Politics

The roots of modern drinking culture can be traced to early colonial conquests in India and the Americas. In his second journey, Columbus brought sugarcane from the Canary Islands to the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and as the slave-powered economy of the New World flourished in the 1600s, sugar production dominated not only Caribbean agriculture, but also European politics.

To reduce wastage from refineries, planters tried fermenting the molasses and distilling them into a spirit, initially called ‘kill-devil’ and later, rum (from ‘rumbullion’, an outdated word for clamor). With dazzling speed, colonial sugar barons became enough of a factor in British politics to lobby for the establishment of rum as the standard spirit on board British ships, replacing wine and beer. Rum had several advantages – it kept much longer than weaker beverages, took less room in the hold, and, with its high alcohol content (57%ABV or 114 proof), was not a threat to the ship’s gunpowder stocks.

His Majesty’s government hailed the novelty for its low cost, unlimited availability, and the good excuse to slam the door in the face of French brandy manufacturers. The French in turn banned imports of rum from their colonies, in a campaign to protect the local wine industry, only to incentivize French colonies to sell their molasses to the British at bottom prices, forcing London to impose additional punitive measures. And while London and Paris threw paper at each other, what did sailors do? They saluted the Caribbean sunset with their evening half-pint of rum.

Meanwhile, in India…

While British admirals, generals, and various opportunists sought ways to subdue the maharajas in India, sailors discovered a more pleasurable way to spend their time in the back alleys of Madras and Calcutta. Locals showed an affinity for an invigorating mixture of arrack (made of fermented rice and coconut flower), water, sugar, lime juice, and spices. Due to its five ingredients, the concoction was known as panj (meaning ‘five’ in Hindi). And while the West substituted arrack with rum, brandy or whisky, bowls of punch are still the centerpieces of any garden party today, which is proof enough of the Royal Navy’s global reach.

The Red Velvet Potion

As with much of this story, the tipsy trail leads us across two oceans and back to the Caribbean, where colonial greed poured half the world into a shaker and produced enough bitter-sweet to last us for centuries.

The 18th century sailor was known to be a bit of an orphan on dry land, and no one was more willing to offer shelter than the brothel, with its cushy beds and carnal pleasures. Lift the curtain of any honorable cathouse (or bagnio as they were called) in the Spanish Antilles, and you found craggy sea-wolves enjoying a chat with quick-eyed señoritas over a glass of sangaree – a blend of madeira, citrus, sugar, spices, and water. Fast forward a couple of centuries (and numerous nautical voyages), and this red-light potion, now known as sangria, is a national drink in both Spain and Portugal. Salud!

The Admiral Mixologist

Another early touch of refinement to hardcore navy boozing was unwittingly made in 1740 by Admiral Edward Vernon, nicknamed Old Grog on account of his waterproof grogram coat. Worried by the effect a pint of undiluted spirit had on a sailor’s discipline (remember the word ‘rumbullion’), Old Grog ordered that the daily ration be watered down. Considering the quality of water on board, this move gained little popularity, forcing sailors to sell their food rations for limes and sugar, in order to make the mixture more palatable.

Born in crisis, the recipe became widely known as grog, but many people today might recognize it as daiquiri (with the water justly omitted) or mojito (with the addition of mint). And although it is disputed whether Old Grog was aware that limes prevented scurvy, both sailors and landlubbers alike adopted grog as a healthy and delicious way to consume stale drinking water.

Proof of Good Standing

Some countries still use the term ‘proof’ to denote the strength of an alcoholic beverage, but the origin of the word can be traced to the British Royal Navy. The crew would test each delivery of rum or gin by pouring liquor on a bit of gunpowder and setting the mixture on fire. If it flared up, it meant the rum contained at least 50 per cent alcohol, hence ‘gunpowder-proof’.

This was a crucial test, not so much because officers worried about sailors not getting stoned enough, but because rum and gin were stored near the ship’s gunpowder stock, where accidental leakages from the barrels could render the gunpowder unusable. Hence, 57%ABV (or 114 proof) was established as the Navy norm and is still known as ‘navy-proof’.

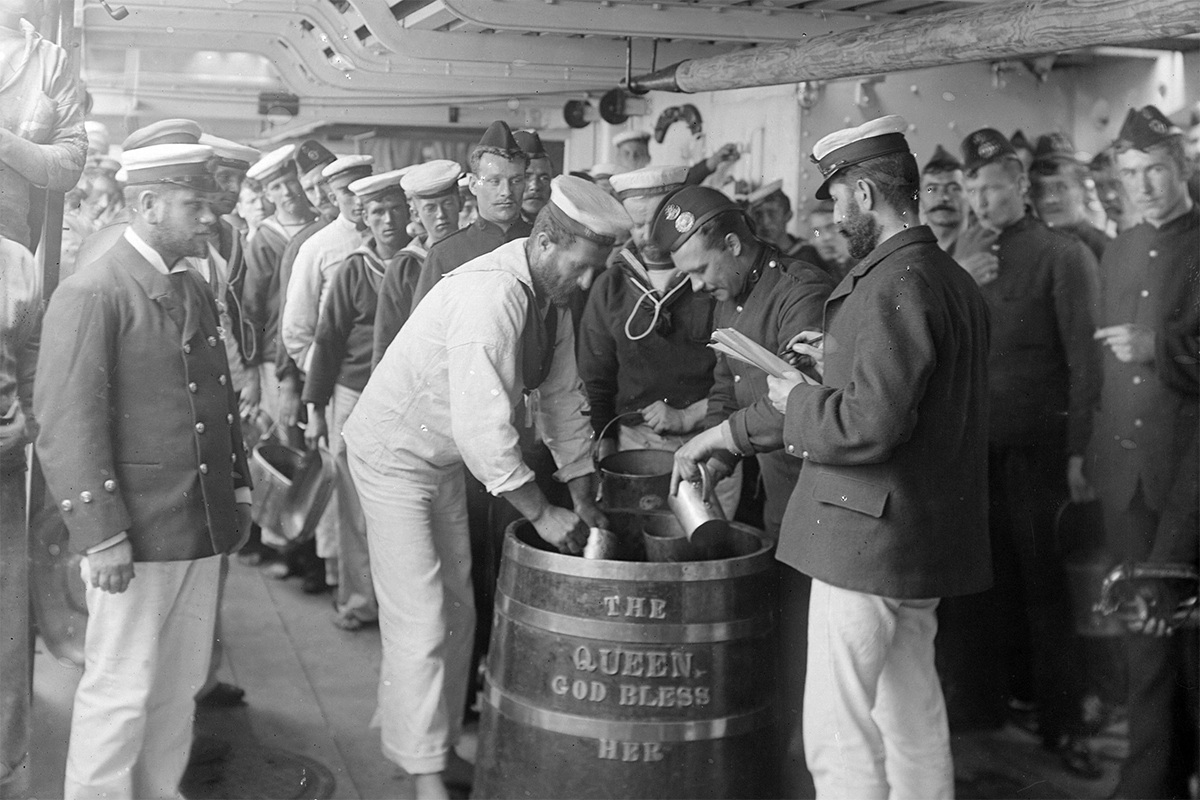

How to Splice a Mainbrace

A classic aphorism in both sailing and drinking folklore, “Splice the mainbrace!” is an order to dispense rum to the crew, still in use to the present day, long after the last navy vessel parted with her rigging. With modern ship crews as sober as church choirs, this coveted command can still be issued on special occasions by the monarch and the Admiralty. And given the prize, we must ask the question – what is a mainbrace and how do we splice one to get a shot of rum?

The mainbrace was the longest and most essential line of the running rigging of a sail ship. and as vessels lost their maneuverability without it, it was a popular target for the enemy during naval battles. Once torn, repairing the several-inches thick mainbrace was one hell of a job, even without bullets and cannonballs hissing all around. The task fell to the most experienced seamen on board, its successful completion being rewarded afterwards with an extra tot. And speaking of brave sailors, we welcome our next guest…

Dutch Courage for the British Sailor

Gin has such a traditional British aura that few people know it was invented by the Dutch. Well, some Benedictine monks in Italy are known to have experimented with juniper-infused moonshine in the 11th century, but since it was advertised as a medicine, it never gained popularity among the population.

Fast-forward to the Thirty Years’ War, with thousands of worn-out British volunteers and mercenaries seeking warmth and comfort in jenever, or what they had nicknamed ‘Dutch Courage’. Gin was the product of a simple and inexpensive distillation method, which the Brits took home with them at the end of the war in 1648.

Gin got so popular on the illustrious island that some decades later it had already gained a reputation as the plague of the century. The English variety had little to do with the Dutch juniper-flavored elixir, being twice as strong and reeking like industrial solvent. Jerry-made private distilleries flooded the cities, as Britain’s poor drenched the sorrows of a hard-knock life in the cheap but potent spirit. And before Parliament had time to restrict the drunken rampage of the nation (with drastic legal measures in 1729, 1736, 1743, 1747 and 1751), a more refined version of this ‘mothers ruin’ found its way into the Royal Navy.

The theory of navy gin’s superior quality is supported by the fact that it was used as a flavor enhancer for a groundbreaking, but horrendously bitter malaria cure – quinine. Brought by the Spaniards from Peru, this extract from the bark of the Cinchona tree soon became indispensable on all British ships bound for India and the Caribbean. The only problem was its repulsive taste, necessitating the addition of water. But as we know, sailors had little love for water and lashed their tonic rations with as much gin as they could find. With malaria thus taken care of, it was high time to tackle scurvy.

By the end of the 18th century, the effectiveness of citrus fruits had been universally established, and in 1867 Scotsman Lauchlan Rose found a way to concentrate and preserve limes in the form of a cordial (known to bartenders the world over as Rose’s Lime Juice). And since Mr. Rose was a ship-chandler by profession, it wasn’t long until his product found its way across the gangplank. Navy-surgeon Thomas Gimlette recommended mixing it with gin to fortify the sailors’ immunity and lift their spirits, immortalizing both Rose’s name, as well as his own. As author and booze-authority Raymond Chandler wrote: “a real gimlet is half gin and half Rose’s lime juice cordial and nothing else.” Hear, hear…

The Hangover

Partly due to scientific developments and largely thanks to unbiased observation, the 1800s brought about a robust dispute about the benefits and perils of drinking on board. It gives energy – true enough – but alcohol is digested in the liver, causing widespread cirrhosis among sailors. In addition, medics and officers began to notice that instead of quenching thirst, liquor could cause dehydration and heat-strokes in tropical climates.

A more immediate and critical problem, though, was the chronic intemperance among sailors and soldiers during the Napoleonic and Peninsular Wars, when sources reported battles being fought by drunkards, harder to keep under control with each day. The result was a gradual but firm change in the attitude toward alcohol, most notable in the reduction of daily rations from a full pint of spirit daily in 1650 to the proverbial ‘tot’ (or 1/8 of a pint) in 1850.

In the 20th century, palatable food and a variety of soft drinks became increasingly available on navy vessels, while more attention was paid to recreation and daily routine, all of which reduced the importance of drink as the only consolation in a sailor’s life. Well-fed crews were not only more productive and disciplined, but also less attached to their daily tot.

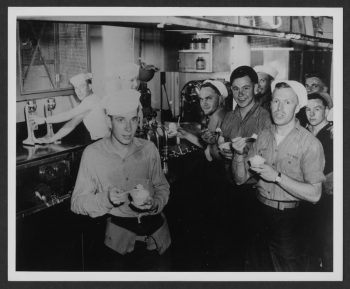

The US Navy was the first to ban alcohol in 1914, years before Prohibition struck the mainland and with a lot more success. One curious result of this was that American sailors, deprived of their little treat, turned their voracious appetite toward ice-cream. US naval history is full of anecdotes, like the sinking of the U.S.S. Lexington by the Japanese, when sailors abandoned ship only after raiding the freezer. Eyewitnesses report men scrambling to the lifeboats with helmets full of ice-cream. The craze pinnacled in 1954, when the Navy fitted a Pacific concrete barge with freezers to serve as a floating ice-cream parlor for smaller vessels, which was such a roaring success that the army built three more ice-cream ships, catering to worn-out troops on the islands of the South Pacific.

In stark contrast, prohibition in the British Navy came about much later and in a rather somber atmosphere. Europe remained predictably indifferent to the fervor of teetotalism in the New World, and it took until 1970 for Britain to make a final decision and bury the age-old naval tradition. And burial is the right word here, as on July 31, 1970 (dubbed Black Tot Day), when the proverbial mainbrace was spliced for the last time on all British Navy vessels, many sailors wore black armbands, on one occasion even performing a burial-at-sea for the empty barrel.

Despite the deep historic roots of the daily tot, it no longer had a place among the complex machinery of modern vessels, with all life regulated by stringent health and safety norms. And even though some nations persisted for a while, most notably the New Zealand Navy, which only abolished alcohol in 2014, temperance is the universal standard on warships all over the world.

And with this, ladies and gentlemen of the high seas, our journey through time is complete. For those of us still standing on our own two feet, let us raise another glass and deliver a final toast to the wind that blows, the ship that goes, and the lass that loved a sailor!

The Shipyard