We all love pirate films and their legions of scraggy, grimy vagrants with knives between rotten teeth. But Hollywood is known for popularizing entertaining stereotypes (quirky, over-accessorized captains were much less common than Disney would have us believe), and once a cliché gets stuck in our minds, little room remains for solid facts. So, Johnny Depp’s famous dreadlocks aside, what was hygiene really like in the Age of Sail?

But first, a few words about the period. While sails took mankind to the seas as early as 2,000 BCE, we are discussing a specific window between the 16th and the 19th centuries CE, when wind-powered ships were at their technological peak and dominated global trade and warfare. And while Austronesians used sailboats four thousand years ago to populate the Pacific, the Age of Sail produced global naval hegemons like Britain, France, Portugal, and the Netherlands. These colonial empires treated their fleets as instruments of wealth and influence, making consistent efforts to improve maintenance of both equipment and manpower. And while scented soaps and cologne were far from anyone’s mind, merchants and navies understood that making money and winning wars was a lot easier when crews did not perish of infectious diseases.

More Than Just Body Odor

Hygiene problems began before sailors even saw the ship. Most recruits in Europe joined the navy through a compulsory practice known as impressment, in which men were literally dragged from the streets, their consent often stimulated by a stiff club to the head. At some point, resistance to this form of recruitment was so strong that navies had to pull convicted criminals out of jail to staff their ships. The result was a nightmare for captains and a heaven for germs. Typhus was called ‘jail fever’ for a reason – many inmates carried the disease on their soiled clothes, transferring it to the healthy sailors in a matter of hours.

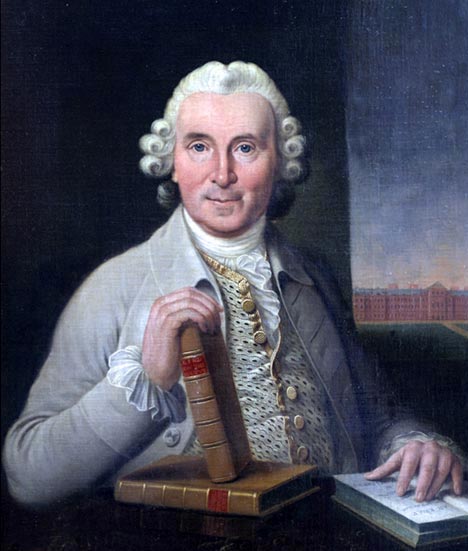

To make things worse, wooden ships were notoriously damp and ill-ventilated. As a porous material, wood was impossible to sterilize, offering the ideal environment for parasites like fleas, bedbugs, and cockroaches – all of them carrying disease and discomfort. But after a long period of germ-infested chaos on the ocean, one man made a decisive step toward eradication of illness on naval vessels. Beginning with a momentous treatise on scurvy in 1753, Scotsman James Lind later addressed the issue of typhus. Even though science was still a long way from discovering microorganisms, Lind had noticed that certain prophylactic measures prevented or reduced typhus outbreaks. In addition to improved ventilation and regular scrubbing of the decks, Lind convinced the Navy to implement “slop ships”. These were buffer vessels, where recruits were stripped, bathed, quarantined, and issued with new clothes, before being transferred to the sea-going ships.

Ventilation and drinking water, however, remained a problem. The 18th and 19th century saw many attempts to provide safe drinking water and better air-circulation, but most technologies proved too troublesome and inefficient. One of these was James Lind’s still (a very Scottish invention), which purified contaminated water through distillation. Its processing capacity was tiny, however, and adding alcohol to water for disinfection remained standard protocol until the age of steam. The ventilation issue proved even more stubborn, with the only meaningful breakthrough coming from the French, who were the first to substitute fixed cowls with a wind sail to divert wind into the vessel’s interior.

Passenger Plights

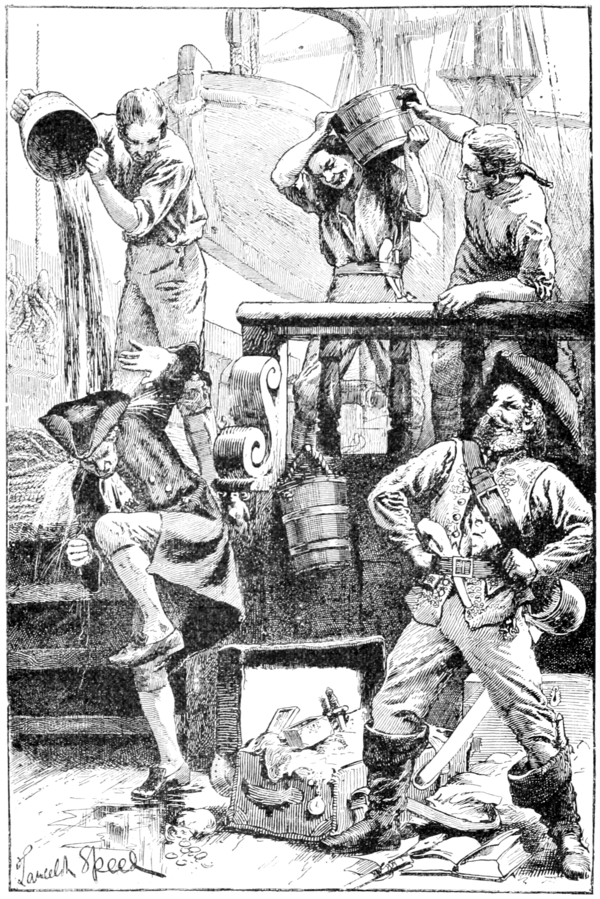

Measures to reduce contagion on naval vessels gradually improved, with each new scientific discovery leading to more hygienic ship design and operation. Conditions on merchant ships, however, remained a bit sloppy. Even on intercontinental voyages, most passenger vessels offered only basic lavatories and no bathing facilities. Conditions were so inadequate, especially in rough weather, that most passengers relieved themselves on the upper decks, sharing the same vinegar-soaked rag instead of toilet paper. As a result, dysentery and typhus remained rampant in the merchant marine, keeping death rates high throughout the Age of Sail.

Rescued by Technology

Another tenacious headache was dampness, as sailing ships were almost entirely made of absorbent and flammable materials. Wood kept humidity high, while fire hazard limited the use of stoves to the galley. And while sailors slept on hammocks, most passengers used straw bedding, which quickly got soaked through, the cold and dampness opening the door to influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. So, despite the occasional disinfection with vinegar and chlorine bleach, conditions on passenger ships remained morbid and unpleasant.

In the end, most of these difficulties were solved by the Industrial Revolution and its rapid innovation. First, steam engines drastically reduced the duration of voyages, minimizing food and water spoilage, as well as limiting the exposure of crew and passengers to disease. Second, steel was easier to cleanse and disinfect daily, while technological advances brought laundry and bathing facilities on board, leading to improved personal hygiene. Finally, heating made modern vessels warmer and dryer, which not only increased comfort but helped prevent disease.

Two problems that persisted well into the 20th century were ventilation and temperature control, with steamship design focused more on letting fumes out than bringing fresh air in. This only began to change with the invention of air-conditioning. Its first marine application was on the Normandie in 1936, while the first fully air-conditioned steamer was the Japanese Koan Maru in 1937.

So, How Bad Did Pirates Stink?

Contrary to popular belief, the Golden Age of Piracy was quite short, lasting less than 80 years in the 17th and 18th century. Thus, the opportunistic, short-sighted, and usually barbaric pirate leaders rarely maintained the operating standards of the Navy, which also included hygienic and prophylactic measures. With frequent battles and a violent lifestyle, the average pirate could not have been preoccupied with his (sometimes her) personal hygiene. So, if I had to make a guess about Blackbeard’s body odor… I’ll pass.

Want to read more? Click here to find out how the navy gave us cocktails!

The Shipyard